I. [1] In his autobiography Interesting Times, Eric Hobsbawm identified an international trend in post-war historiography: “[…] in spite of patent ideological differences and Cold War polarization, the various schools of historiographic modernizers were going the same way and fighting the same adversaries – and they knew it. […] In other words, they wanted a much broadened or democratized as well as methodologically sophisticated field of history” (Hobsbawm 2002, 288). West German historiography inscribed itself within this general development. Among the hallmarks of this renewal in the Federal Republic was Historische Sozialwissenschaft (history as social science). In its formative phase, this new historiographical current was characterized as an Oppositionswissenschaft vis-à-vis the more traditional history of ideas and politics (Iggers 1997; Schulz 1989; Raphael 2003). At the same time, Historische Sozialwissenschaft stood in a relationship of both distance and proximity to the current of West German social history as Strukturgeschichte (structural approach of social history) of the 1950s and 1960s (Gironda 2021, 21-46).

First, despite the wealth of variants in programmatic writings and research practice, Historische Sozialwissenschaft and Strukturgeschichte were united by a generic concept of social history. This served as a window for cooperation and the continuation of a dialogue. Both approaches emphasized a common interest in social history without a concrete definition of the term – except for the fact that social history questions should primarily be about investigating the history of society, more precisely of social structures, processes, and agency in the narrower sense, as well as of the transformation of entire societies and collective behavioral dispositions. As a general history, they aimed at a specific way of looking at the history of whole societies. This social-historical minimum is reminiscent of Werner Conze’s classic scientific-theoretical basic position (Conze 1966, 19-26), even though the fundamental discussions in the 1970s about the ubiquity of “structures” and a highly unspecific and abstractly formal character of social history’s structural approach indicated striking methodological-conceptual and thematic-theoretical shifts (Kocka 1977; Welskopp 1998, 173-198).

Second, the distinctions resulted from the plea of historical social science for an adequate “use of theory”. Thomas Welskopp articulated this point: Historische Sozialwissenschaft understood Strukturgeschichte as a pioneer, but a deficient one. Accordingly, the decisive paradigm shift was only undertaken by Historische Sozialwissenschaft (Welskopp 2002, 296-332). The first empirical studies of the new social history between the mid-1960s and early 1980s mainly focused on analyses of economic and social macro-processes: modernization in the late 19th century, social stratification, industrialization, social groups and their interest representations.

Third, the formative and non-negotiable moment of distinction in the field of social history arose at the level of the entanglement of science and politics. Without considering the entanglements of intra- and extra-scientific factors, neither the understanding of science in critical social history nor some of the sharp edges in the debates on German history before 1933 can be explained. The attempt to establish Gesellschaftsgeschichte (history of society) as a “regulative concept” contoured the distinctions among historians precisely “with regard to the influence of politics on science” [2]. At the end of the 1970s, Jürgen Kocka characterized the critical and partly dismissive attitude toward Gesellschaftsgeschichte as a defensive strategy against its inherent ideology-critical-enlightenment dimension, because this dimension “at the same time also contains a potential for criticism within science, since the uncovering of socio-economic conditions of historical phenomena inevitably results in a not inconsiderable tension with the self-understanding of other approaches and directions methodologically affected by it” [3].

As Dieter Langewiesche noted a few years ago, the project of critical social history consisted of practicing a therapy for the present by analyzing the past (Langewiesche 2006, 67-80). Through the explication of the past and the analysis of the causes of the fateful year 1933, the present was to be “purified” in terms of historical therapy. Therefore, Historische Sozialwissenschaft focused primarily on the question of the structural conditions of historical continuities. Historische Sozialwissenschaft developed a research program that aimed at explaining the causes of the rise of National Socialism, analyzing the German path to modernity, and determining the continuity of structural factors and pre-conditions in modern German history, by means of an analysis of the various political constellations of the late 19th century and through an implicit comparative perspective. The thesis of an alleged “German divergence from the West” was produced through the identification of long-term structures and processes (including the absence of a completed bourgeois revolution, the political influence of pre-modern elites, the persistence of illiberal elements in German culture, weak parliamentarization, etc.) which, in addition to short-term factors (Germany’s defeat in World War I, the sharpening of class conflicts, the radicalization of the political spectrum), contributed to the collapse of the Weimar Republic. From the early 1970s onward, the critical Sonderweg thesis became the synthetic cipher of Historische Sozialwissenschaft (Sheehan 2005, 150-160). The controversy surrounding Hans-Ulrich Wehler’s influential book Das Deutsche Kaiserreich (Wehler 1973) documents how this publication soon became the locus classicus of the Sonderweg thesis, and how this thesis represented a kind of training ground for accusers and defenders of a historical science that saw itself as emancipatory (Nipperdey 1975, 539-560; Hildebrand 1976, 328-357; Conze 1976, 507-515).

In the second half of the 1970s, Historische Sozialwissenschaft found in the newly-established Bielefeld University the location for its programmatic elaboration. Soon, the term “Bielefeld School of History” became internationally known. Exactly fifty years after the Faculty of History started its activities at Bielefeld University in 1973, the question remains whether one can really speak – even temporarily – of a “Bielefeld School” (Budde 2011, 56-86; Raphael 2015, 553-558; Hitzer and Welskopp 2010, 13-32; Stelzel 2019). Was there really a “Bielefeld School of History”? Or was it rather a question of a certain academic milieu, a specific style of historiographic approach, or even a historiographical laboratory? Is it possible to speak of a Denkkollektiv (thinking collective) that shaped a comprehensive bond and coherence among the actors involved in terms of content as well as socially and politically, and which did not merely share similar thematic positions and epistemological interests (Fleck 1935, Etzemüller 2001, Klausnitzer 2014)? Were the methodological premises, the historiographical practices, as well as the scientific production sufficiently distinctive, uniform, and influential to speak of a new paradigm? Beyond the appellative character of Theoriebedürftigkeit (the need for theory) of history, are there “scholarly” or group-compliant connections in the theoretical assumptions about historiography made by Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Jürgen Kocka, Hans-Jürgen Puhle, Sidney Pollard, Peter Lundgreen, Reinhart Koselleck, Wolfgang Mager, and others? So far, these questions have only been illuminated in rudimentary form.

In the following, I will argue that, contrary to what is often assumed and written, this was not a paradigm shift, let alone the establishment of an academic school – the “Bielefeld School” – but rather the emergence of a specific academic milieu whose internal coherence was based on the convergence of two developments: on the one hand, a flexible framework for a shift to Sozialgeschichte (social history) and Gesellschaftsgeschichte (history of society), which allowed for and even required many theories and approaches (a “school” would have been too narrow and even obstructive for this); on the other hand, a special esprit de corps that enabled the institutionalization of this interpretation of historical science. Both – the framework program and the consistently pursued institutionalization in the context of a young Reformuniversität (reform university) – mutually reinforced each other. And out of the mutual reinforcement of these two developments a specific, a “Bielefeld” milieu developed, consisting in a cohesive, but not homogeneous, network that shared a similar methodological premises and thematic focus (society) and sought to establish through joint action the Historische Sozialwissenschaft as a renewal of West German historical science. The Bielefeld milieu acted as a kind of “greenhouse” for Historische Sozialwissenschaft and its enhancement.

But, first of all: What is a scientific school and what are its distinctive traits?

Sociologists and political scientists identify the emergence of scientific schools through differentiating features in the formation of structures within the scientific field (Fischer and Moebius 1999; Dayé 2016, 128-133; Bleek and Lietzmann 1999). In these research discussions, the emphasis is placed on either cognitive, communicative, or organizational aspects. A distinction is commonly made between a school of thought (Denkschule), consisting of a set of interrelated ideas and positions, and a more institution-based understanding of the concept of school that focuses predominantly on social organization. In the first case, the formal and substantive seclusion of a stable social group is stressed, which, through common epistemological interests, applied methods, and theories, internally shapes and disciplines a kind of collectively shared “style of thinking”, while externally acting as a distinguishing factor from other locatable groups of scholars. Moreover, from this research perspective, school context and school affiliation, a minimum degree of cognitive coherence, as well as the intergenerational transfer of a specific “leading theory” are constitutive. Thus, “student bonding” is an important marker for the long-term establishment and perpetuation of “school building”. An institutional theory explanation, on the other hand, stresses more heavily that an influential scientific paradigm, a theoretical guiding idea, can only have a schooling effect if it is accompanied by the formal and informal involvement of actors in an institutionalized context of research, teaching, publications, and public presence.

Based on these considerations, the following contribution analyzes the institutionalization process of the “Bielefeld School” which took place on different levels between the 1970s and the end of the 1980s, by focusing on: (I) the setting or the enforcement of a scientific profile building; (II) the strategy for personnel policy with regard to the filling of new professorships; (III) the planning and execution of research projects within the Bielefeld faculty; and (IV) the founding of publication organs, which were supposed to make the project of a theoretically reflected social history visible in the field of historians. In addition to these topics, the question of stabilizing an academic school in general is also addressed (V): did a group of young historians establish itself in the 1970s and 1980s who pursued a research perspective that thoroughly aligned with the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological views of the “teachers”? To what extent did historians trained in Bielefeld understand their own work (dissertations and postdoctoral theses) to be in continuity with or in distinction from that of the “masters”?

I. Founded in 1973, the faculty initially consisted of seven university teachers (five professors and two akademische Räte) and sixteen research assistants. Teaching activities began in the same year, but the work of the Bielefeld historians did not start in the best of circumstances. The university had been going through a “structural crisis” since the mid-1970s due to the generally precarious economic situation. In 1975, the Rector, Karl Peter Grotemeyer, had to introduce tough cost-cutting measures, which led to delays and even abandonment of some reform plans. Initially, the history faculty was also affected by these cuts. At the end of 1974, Jürgen Kocka in his function as a dean wrote to the Bielefeld Rector about the difficulties the faculty was having in being able to fulfill its functions, and after two years of a development standstill he demanded that the increase in positions proposed in the draft budget for 1975 and 1976 be approved [4]. In doing so, he described an internal faculty situation of growing “resignation.” By 1974, the faculty had received only 50% of the positions originally planned by the founding committee, but was nevertheless participating in two teaching programs, namely history and, together with the Faculty of Sociology, social science. It thus supervised more than 300 students and expected an increase of 50% in the following years.

In 1974, the faculty adopted a self-determined research focus, specifying the generic reference to social history as a programmatic guideline that had already been included in the faculty’s founding conception a few years earlier [5]. A sort of “framework program” was defined – one flexible enough to offer room for all actors involved. What is striking in this concept paper is the constant reference to all those formulations with which Wehler and Kocka had previously led the internal discussion on a renewal of social history in the first half of the 1970s (Kocka 1986, 97-108; Wehler 1973). They spoke of social history as a systematic orientation to distinguish it “from approaches based only on the history of events or persons” [6]. Scientific postulates of their own were formulated, which were to take into account “the changing interdependence of society, economy, politics and culture” under “theoretical anticipations” (theoretische Vorgriffe) from history and the social sciences and by means of both “historical-hermeneutic and social-scientific methods”. This implied that historical phenomena were to be “understood in their socio-economic, socio-political and socio-cultural context” [7]. The emphasis was on the critical application of questions, methods, theories, and models from the social sciences in research practice. In addition, new methods such as “quantitative statistical methods in economic history, historical demography, or source text analysis” [8] should be tested, while comparative approaches should receive major attention as well. Finally, a detailed reflection should involve conditions, characteristics, and consequences of historical work. In sum, the faculty founders reverted to a broad conception of social history which could be applied to various fields in the practice of historical work. Sozialgeschichte could thus be understood not only as a subfield (Teilbereich), i.e., as an analysis of social groups, strata, and classes in their relationship to economic development, politics, and culture, but also as a special form of overall social observation, precisely as “history of society“ – even if the key concept of Gesellschaftsgeschichte was not explicitly included in the strategy paper.

The homogeneous interest in sharpening a social-scientific orientation as a kind of Bielefeld trademark in the context of West German historiography can also be seen in the close linking of the research agenda with the teaching curriculum. In the first faculty regulations for the study program, adopted on 23 April 1974, historical science was conceived in a broader sense as a social science. The Bielefeld learning concept was intended to make clear to prospective historians that “historical science [cannot] disregard the social contexts in which it itself stands, by which it is conditioned, and on which it acts” (Rüthing 1994, 146). Furthermore, “it is part of the historian’s task, and also of the study program, to reflect on this multifaceted connection between work in historical scholarship and contemporary social criticism and to take it into account when selecting topics” [9].

In the curriculum developed along this line of thought, the study areas were designed to have a clear orientation toward theories as a means of historical argumentation. Accordingly, a number of course formats were planned to convey the basic understanding of history as a historical social science. The formats included, for example, the Basic Seminar I, on the theory of historical structures and processes, as well as the Basic Seminar III, on the theory of science and subject didactics, which aimed at creating the basis of history didactics (Fachdidaktik) through a “self-reflection of historical science with regard to its theories and traditions, its position in the system of sciences and its position in the framework of political and social relations” [10]. Compared to all other universities in the Federal Republic, the conception of the study program in the first phase was very specific to Bielefeld. The conventional proseminars were replaced by a Basic Seminar of six weekly hours over two semesters, taught by three (after 1982 two) instructors, and spanning across epochal boundaries. This type of program was largely premised on the basic idea, advocated by the departmental commission during the founding phase of the university, that the periodization question should be structured according to factual aspects instead of “only comparing the numerous epochal determinations” – as Koselleck later expressed it to Dietrich Gerhard [11].

The Bielefeld group of historians was indeed self-confident. Within a few years, there was a growing conviction that something new and innovative had emerged in Bielefeld within the framework of West German and international historical scholarship. Any external intervention that threatened to undermine the basic structures of the 1974 framework was perceived as a kind of deviation from the group’s own practiced scientific specificity. The goal consisted in defending the faculty’s own profile formation against both higher education policy decisions of the state and internal university calls to redesign the curricula. It is therefore not too surprising that in 1978, through Wehler as public spokesperson, the faculty radically rejected the so-called Zusammenführungsgesetz (“merging law”) that as of 1 April 1980 would re-organize the Pädagogischen Hochschulen (“pedagogic colleges”, PH) in North Rhine-Westphalia within the universities. In his “philippic” published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Wehler saw the state government’s action as a political-bureaucratic arrangement that contained no understanding of the academic differences between PHs and universities (Wehler 1974). Without mincing words, he wrote of the end of “performance-based education” at the universities, of the unsustainable equalization of the PHs with universities, finally culminating in the polemical remark that PH docents usually could not demonstrate international, subject-specific standards and research competencies. He thus warned against the “quasi-academic national uniformity mush” caused by the entry of PH docents and against a “par ordre du mufti” – imposed bureaucratic and “deeply intolerant homogenization compulsion” of the university system. Within the faculty, the Düsseldorf plan was seen as a significant detriment to any future research developments [12].

The same logic guided Wehler’s intervention against the plans of the Bielefeld Prorectorate for Teaching, Student Affairs, and Continuing Education concerning the redesign of courses of study for the schoolteacher’s curriculum in 1981. In its concept paper, the Prorectorate tried to persuade the Faculty of History to redesign its curriculum for didactic and career-prognostic reasons – e.g., abandoning intermediate examinations – and because of the guarantee of greater didactic freedom for students – e.g., strengthening the self-organized student groups in terms of examination regulations. In his private letter to the rector, Wehler described the programmatic lines of the Prorectorate as an “irritating devaluation of specialist science” (Fachwissenschaft) and even mocking it as an expression of the “arrogance of didactological excellence” [13]. As a consequence, according to Wehler, implementing the new guidelines would have meant “destroying the university as an ensemble of disciplines and attempting a questionable unification through didactics and professional practice on these ruins” [14]. However, wrote Wehler, summarizing the basic tenor of his letter, if Bielefeld wanted to establish itself as an innovative science location in the long run, there was nothing left to do but to insist very decidedly on the “priority of specialist science in research and teaching”. Anything else would only be “scientific self-castration”, to take up a formulation used by Wehler in this letter.

II. Since the second half of the 1970s, a convergence can be observed between the 1974 strategic “framework program” and faculty personnel policies pursued in filling new professorships. For example, Peter Lundgreen, who had already been working as a research assistant in the university profile “science studies” (Wissenschaftsforschung) and as a lecturer (Privatdozent) with the historians since 1975, was offered a chair in the History of Science in 1979. Lundgreen’s studies on education and technology in Prussia in the first half of the 19th century, his investigations of the relationship between economic growth and education in the process of industrialization, and his epistemological interest in the central question of how different subject areas (education and social structure, education and family, education and politics) could be brought together in a systematic analysis of social change, were functional to the institutional concept of the history of science which the faculty had worked out some years earlier (Lundgreen 1975; Lundgreen 1973). They were looking for a historian who did not deal with the history of ideas of his own discipline as an object of scientific reflection, but who advocated for interdependencies between science and the development of society as a whole [15].

In academic personnel decisions, there was no shying away from confrontation with other faculties in terms of content, as documented by the appointment of Hans-Jürgen Puhle as Johann Hellwege’s successor to the professorship of Iberian and Latin American history. In that case, the conflict between the research program and the strategic interests of the faculty and those of the working group and the representatives of the university subject profile “Latin American Studies” was so intense that the latter had written a special declaration of vote with regard to the appointment procedure. It was followed by another one presented by student representatives appointed within the faculty conference and in the chair appointment committee (Berufungskommission) [16]. The conflict had arisen after the voting professors of the faculty conference had rejected the initial order (Gerhard Brunn/Hans-Jürgen Puhle) as almost unanimously proposed by the nomination committee (8 yea, 1 nay, 1 abstention) and eventually voted for a change of the order with Puhle in first place [17]. Reinforced in their decision by the external reviews of Magnus Mörner from the University of Pittsburgh, Friedrich Katz from the University of Chicago, and Hans Werner Tobler from the University of Zurich, almost all representatives of the faculty conference emphasized Puhle’s substantive connectivity to the general scholarly discourse of the faculty [18], which then ultimately prompted the Rectorate to accept the exchange of candidates in the first two places on the appointment list.

The extent to which the eventual implementation of the program in the 1970s depended on a faculty strategy shared and supported by the central university governance is attested to by the appointment of Sidney Pollard to the chair of economic history in 1980. The understanding of social history in the concept paper of 1974 reaffirmed a basic principle established during the internal debates in the 1970s, according to which social history “usually is closely related to economic history and in this respect should often be regarded as an integrated part of the subject of social and economic history” (Kocka 1982, 20). In this context, social and economic history meant primarily the socio-economic analysis of general history.

Although it took almost a decade before the faculty was able to establish a professorship in economic history, already in the early 1970s Wehler and Kocka had an ideal profile in mind for the scholar to be appointed to that position. They did not want a pure economist, but an accomplished economic historian with a distinct interest in social-historical issues, because “in a faculty that conducts history as a historical social science and has a social-historical focus, […] competent social-historical research is not possible without intensive inclusion of the economic-historical dimension,” as Jürgen Kocka stated in 1974 [19].

Wehler contacted Sidney Pollard. Pollard had had to decline the offer of a post at the University of California, Berkeley, at the end of 1971 because the US authorities denied him an unlimited work permit due to his former membership in the Communist Party of Great Britain (Holmes 2000, 513-534; Berghoff and Ziegler 1995, 1-14; Renton 2004). In the late fall of 1973, Wehler approached Pollard to sound out his willingness to come to Bielefeld. At that point, he was not able to give any precise information about the time frame; with the aim of maintaining contact, he had merely suggested that Pollard first familiarize himself with the situation in Bielefeld through a visiting professorship [20]. Pollard accepted Wehler’s suggestion, and the following year he taught two seminars in Bielefeld on English economic history in the early 20th century and on the history of the English Industrial Revolution. In the following years, Pollard’s relationship with the Bielefeld group of historians intensified. In the academic year 1978-79, he took a one-year research fellowship at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research (Zentrum für Interdisziplinäre Forschung, ZiF) at Bielefeld University, where he worked on his project on industrialization in 19th-century Europe. The Bielefeld faculty showed interest in the historian from Sheffield for a number of reasons. On the one hand, he was an internationally renowned economic historian. On the other hand, his research focus was considered to be in line with Bielefeld’s strategic profile for the chair of social and economic history. When Wehler wrote the laudatory recommendation for Pollard in 1980 in the context of the appointment procedure, he described his English colleague – as did Wolfram Fischer in his external expert report (Gutachten) – as an economic historian who, in addition to his central fields of research on the industrial revolution in England (capital formation, investment issues, the formation of the entrepreneurial and managerial classes, changes in entrepreneurial organizations, etc.; Pollard 1959, Pollard 1965; Pollard 1962; Pollard 1974) and comparative continental European economic history, had from the very beginning, with his social history of the Sheffield labor force, “investigated the social historical dimension of important problems” [21]. Therefore, Wehler continued, Pollard “is not only an economically inspired economic historian, but he has a keen sense for the social, socio-political conditions, and consequences of the industrialization process” [22]. And further: “In the context of his economic-historical work, he has also always understood how to combine systematic approaches to economics, theoretical interpretation, and empirical foundations in a successful way” [23].

Following procedure, Pollard was in first place on the appointments list (Berufungsliste). The only obstacle to his appointment could have been a formal one. In 1980, Pollard had passed the usual age limit of 50 to be eligible for tenure (Beamtenstatus), and, moreover, he was a British citizen. From the beginning, however, the faculty had been careful to devise an argument to get around this formality. Already in his laudatory recommendation, Wehler had drawn attention to a “political” issue in connection with Pollard’s appointment: the aspect of “a subtle political reparation” (Wiedergutmachung), as he called it [24]. He referred to the fact that in 1938, as a boy, Pollard had been forced to flee from Nazi-annexed Austria and seek refuge in London, while his parents were deported and murdered in 1941. This argument was emphatically taken up by the then Dean Christoph Kleßmann in his communication to the Rectorate, pointing out that possible formal problems (age limit and lack of German citizenship) should be considered in relation to Pollard’s unique biographical circumstances: “Mr. Pollard comes from a Jewish Viennese family, was just able to escape to England in 1938, and then began his academic career there under difficult conditions. In this respect, this appointment could also be a piece of ‘political’ reparation” (Wiedergutmachung) [25]. The Rectorate supported the faculty’s argument for the cause Pollard and approached the then Minister of Science in the Rau cabinet, the Social Democrat Reimut Jochimsen. At the same time, in its communication with the Minister, the Rectorate mentioned its intention to appoint George Ettlinger, another scientist of German origin who had been forced to emigrate to England in the 1930s, as professor of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, then at the Institute of Psychiatry of the University of London. For his part, the Minister strongly supported the Bielefeld initiative in both personnel cases and asked his party and cabinet colleague, Finance Minister Diether Posser, to personally seek a formal solution in his Ministry that could meet Bielefeld’s request. For, he wrote, “although it is necessary to protect the state from assuming unreasonable utility burdens, in particularly serious cases, consideration of other preeminent interests must not be omitted” [26]. And in the case of the Bielefeld initiative, the Minister continued, it was not only a matter of two scientists with an international profile, but also of two people who had been victims of National Socialist injustice, so “the state of North Rhine-Westphalia has at least a moral obligation not to be too petty here” [27].

III. In terms of the goals formulated in the faculty’s “framework program”, it can be seen that in their research projects Bielefeld historians kept the field of social history open to a variety of theoretical and methodological suggestions, basic assumptions, and viewpoints. If there was one guiding concept that circulated most clearly in the academic milieu of the faculty in the 1980s and early 1990s – notwithstanding the differences in the scholarly self-image of individual faculty members – it was surely that of a “social history in extension” (Sozialgeschichte in der Erweiterung). The Bielefeld academic milieu of social history took a far less hermetic position than was often portrayed by critics. This was evident in the Collaborative Research Center (Sonderforschungsbereich, SFB) Nr. 177 Sozialgeschichte des neuzeitlichen Bürgertums: Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich, established in 1986 through funding by the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG), and for the Graduate School Sozialgeschichte von Gruppen, Schichten, Klassen und Eliten, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation since the spring of 1988, and, not least, in the project Moderne Nationalismusforschung: Deutscher Nationalismus vom späten 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts in vergleichender Perspektive, also funded by the Volkswagen Foundation in 1992 and headed by Wehler. In the conception, elaboration, and completion of all these projects, the emergence of cultural history did not go unnoticed. In some cases, as with the original project description on modern nationalism, one can observe a moderate opening toward cultural history in so far as the project was intended, at least in Wehler’s conception, to take up the need to include “soft cultural problems” in the analysis of “harder” phenomena of social economy and politics (Gironda 2002, 11-30).

For the funding of early career researchers, the focus was primarily on the traditional research areas of social history. The Graduate School initially focused on reconstructing and analyzing the causes, structures, conditions, and consequences of social inequality over the course of time [28]. The proposal, on the one hand, presented its goals as the application of a socio-economic and legal-political understanding of inequality; on the other hand, the concept paper emphasized that social groups are formed through highly complex relations of inequality which are shaped to varying degrees not only by income, wealth, political power, or law, but also culturally via education, upbringing, age, reputation, gender, origin, etc. Hence there was an interest in productively incorporating those approaches that “focus even more attention on inequality dimensions such as gender, age, and ethnicity” [29]. The paper signaled a certain openness to questions, methods, and topics from gender research and social anthropology – or, as can be read in the application: “In the future, it will be important, among other things, to take up and productively process these impulses emanating from social anthropology and ‘women’s history’ more strongly than before” [30].

Since the early 1980s, there was definitely an interest to enter into a dialogue with some variants of the cultural turn. In other words, the relationship between social history and cultural history was a dialectical one, even if the Bielefeld historians repeatedly emphasized that any cultural-historical approach would fall far short without taking social-historical dimensions into account. They were, however, quite interested in integrating the more recent historiographical trends on the history of cultural perception, experience, symbols, and Weltbilder into history as social science without emphasizing them unduly. However, they all adhered to the fundamental position that historical science was always something more than and different from fictional literature.

This can also be seen in regard to the “exhausting affair” (Hettling 2008, 219-232) of the Bielefeld social historians’ research on Bürgertum (bourgeoisie), which not only ultimately opened up social history to a cultural-historical approach without fear of contact, but through this opening also modified some central premises from its own special research proposal (Sonderweg, Bürgertum as a social class). The fundamental aspect, however, is that the “Bürgertum Project” was already conceived in its original structure along a broad thematic and methodological research interest [31]. All too often, historiographical reconstructions of the Bielefeld Collaborative Research Center have offered a one-dimensional reading that suggests the project was merely an interpretation of German history against the backdrop of the emergence of National Socialism (Mergel 2019, 83-106). The intention of the project would have been to make the Bürgertum the subject of a political social history in the context of the discussions about the German Sonderweg. However, analyzing the discussions conducted within the faculty during the development and completion of the project, three things become apparent.

First, the Sonderweg thesis, which had often been referred to as a less appropriate catchword in the internal faculty papers, turned out to be a kind of Baukastenargument (a modular argument). From the point of view of the actors involved, the focus on the Sonderweg thesis initially enabled a research strategy based on comparison as the guiding methodological approach. Since the early 1980s, among the various criticisms of the variants of the German Sonderweg was the argument that its proponents had basically interpreted German history from a comparison with “the West”, without, however, being able to base this interpretation on truly comparative studies of the bourgeoisie in France or in England [32]. For Jürgen Kocka, therefore, any interpretation of German history along the Sonderweg argument, as well as criticism of it, would remain merely hypothetical without systematic comparative studies: “Comparative studies of this kind therefore promise significant returns and results that may relatively quickly confirm, invalidate, or modify central and controversial pivots of our picture of recent German history” [33]. From the outset, however, it was clear to all participants that an application would only be successful if projects on the medieval and modern age could highlight the Sonderweg thesis from a long-term perspective. Possible constellations for diachronic comparisons were discussed in order to avoid an evident concentration on the last third of the 19th century, especially in the process of proposal writing. For, as far as German peculiarities in modernity are to be researched, “their roots are likely to be sought in the pre-modern world of Old Europe” [34]. The questions were to what extent, in which respects, and due to which constellations specific class or “bourgeois” traditions in the late medieval or early modern urban bourgeoisie had influenced the Bürgertum history of the 19th century.

Second, however, an attempt was made to imprint the overall project on a perspective beyond the narrower field of explaining National Socialism, so that “inner unity and the outer demarcation of the bourgeoisie were to be clarified”. On the one hand, it would be a question of how the bourgeoisie could be defined as a social formation over the course of time. On the other hand, the contexts should be explicitly elaborated in which Bürger and Bürgerlichkeit could become objects of emphatic approval and fundamental criticism since the 18th century [35]. According to the Bielefeld historians, every public controversy and political discussion about the concepts of Bürger and Bürgerlichkeit referred historically to a fundamental dimension of European modernity, which “Max Weber had tried to grasp as the unfolding of occidental rationalism and Norbert Elias as the process of civilization” [36]. Therefore, the topic of the Bürgertum gained importance in the proposal considerations and hypothesis formations of the Bielefeld historians in the sense of clarifying both a specifically assumed ability of Western European societies to modernize and their inner tensions and ambivalences (hopes for progress vs. inhibitions of progress).

Third, two further aspects proved to be consensual within the faculty. The first was the observation that historical research on the history of the Bürgertum showed a considerable deficit in comparison to research on the history of the lower classes. Here the actors involved recognized a great opportunity to pursue the topic as a kind of experimental field in which the methodological and theoretical interests present in the faculty could be tested on broadly uncharted ground. At the same time, the topic offered the necessary separateness and open-mindedness to pursue social history topics in the narrower sense and to integrate political, economic, and cultural history subprojects as well. Thus, during the application process, not only subprojects were desired that made explicit use of the repertoire of social science models and theorems (from sociology, social stratification, and class formation to the analysis of interest groups). Sub-themes that integrated more recent cultural-historical, cultural-sociological, or social-anthropological suggestions into the social-historical views as well as in combination with structural and process-historical approaches were also included. In particular, sub-projects considered the role of symbolic behavior or class-specific cultural characteristics determining the inner differentiation of the bourgeoisie as a social formation and thus contributing to group formation via homogenization or demarcation tendencies.

IV. A central instrument for establishing critical social history as an independent direction within the historical field in the Federal Republic of Germany was the strategic founding of publication organs. These included the series Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft from 1972, as well as the journal Geschichte und Gesellschaft from 1975, both published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (Blaschke and Raphael 2007, 69-109). Over the years, these publications have changed significantly, opening up to the different methodological demands of cultural history and, in the last two decades, of transnational and global history. In a certain sense, they have become more and more generalist.

Still, a review of the first two decades of their activity reveals clear agreement with the original programmatic line of Historische Sozialwissenschaft, also with regard to the idea of integrating new impulses of thought and points of view. Gerhard Albert Ritter has correctly noted that the six-page programmatic editorial of 1972 for the Kritische Studien, which was signed, beside its main author Jürgen Kocka, also by Helmut Berding, Hans-Christoph Schröder, and Hans-Ulrich Wehler, is essentially a political text that clearly distances itself from the conventional traditions of German historical scholarship (Ritter 2011). Jürgen Habermas had the same interpretation of the editors’ intentions after reading the prospectus that Wehler had sent him before the start of the project with the request to make “a discreet advertising for the series” [37]: “I find this demarcation of a critical historiography from the usual and from the nonsensical so exquisite that I circulate the paper in several places” [38]. The authors sought a transformation of the self-image and role of historical scholarship in society. Instead of the affirmative and stabilizing functions that had dominated to that point, which in several respects German historiography had fulfilled under previous social and power systems, the emancipatory and enlightening function of historical science was to be in the foreground of historical thinking. In concrete terms, this meant a critical examination and “questioning of politically directly usable historical myths (Dolchstoßlegende in the Weimar Republic, interpretation of the Nazi Reich as a «Betriebsunfall»)” [39]. This was “just as important as the gradual revision of politically only mediately relevant historical interpretations (Bismarck’s image, causes of the First World War)” [40]. However, this required – according to the final consequence of the concept of criticism – distancing oneself politically and methodologically from the established main lines of one’s own specialist tradition, and especially from its “ideological Staatsfrömmigkeit (unquestioned loyalty to the state)”, the concentration on political and event history, and the concept of understanding what they were based on. For this bundle of problems led to an uncritical national-political identification of history as subject and discipline in service of various ruling systems. According to the authors, two wars and one dictatorship would have contributed to “questioning or at least reducing the national-political integrative function of historiography and, by discrediting the state, to freeing the view, even in German historiography, for other powerful social, economic, historically forces” [41]. So the editors considered the book series a platform to advance their new theory-oriented and social-historical principles. The volumes were to leave behind any semblance of late historicistic and neopositivist analytical grids in favor of a research perspective that sought to link hermeneutic and structural-historical methods. Ultimately, they emphasized that individual actions and decisions were conditioned by supra-individual social structures and processes.

In the first decade of its existence, the book series can be seen as a mix of dissertation theses and monographs, as well as collections of essays by historians already established in the guild. The common thread was a clear emphasis on economic and social history or on works that championed issues, theories, and methods of social science in historical practice. The only exception was the publication in 1976 of a volume of essays by Thomas Nipperdey, which Wehler himself promoted and in this context expressed to Winfried Hellmann: “At the moment, I am still corresponding with Nipperdey, who, notwithstanding his right-wing development, does, after all, produce quite excellent work” (Blaschke 2010, 473).

The publication of Hans Rosenberg’s Politische Denkströmungen im deutschen Vormärz in 1972, which collated his essays on the history of ideas from the 1920s, was, on the other hand and on closer examination, entirely compatible with the programmatic principles of the series (Rosenberg 1972). Rosenberg’s view of the history of ideas focused primarily on Zusammenhänge (contextual connections), rather than on individual persons or ideas as in the classical tradition à la Meinecke. Ideas were eminently important in the historical process “as soon as one traces their social and political functions and their event conditionality” (Rosenberg 1971) [42]. In its programmatic guideline, Historische Sozialwissenschaft primarily contested the lack of “ideology critique” in the conventional tradition of the history of ideas. To this end, they wrote, insofar as the history of ideas is pursued in isolation, “[it] easily fulfilled a displacing function by allowing the exploration of the intellectual heights above the valleys where the unconsidered interests of everyday life collided” [43]. What they advocated – and this differed little from Rosenberg’s position – was the pursuit of a social history of ideas, or the integration of the history of ideas into social history. This meant a “transformation [of the history of ideas] into a history of collective mentalities and ideologies” [44]. Therefore, the history of ideas could also assume a critical function with regard to ideology. On a programmatic level, this can be interpreted as an attempt to trace ideas back to material constellations of interests, or rather to emphasize the basic premise that socio-economic conditions are constitutive for ideas.

Meanwhile, the fact that the founding of this book series was perceived in the mainstream of the historians’ guild (Historikerzunft) as a platform for profiling and distinguishing the practices of a younger cohort of scholars is shown by a rather bizarre episode in 1974, in which Wehler and Theodor Schieder were involved in the occasion of the publication of an anthology on organized capitalism edited by Heinrich August Winkler (Winkler 1974). This publication represented a first collective attempt to explore modern industrial societies with a more far-reaching, partly theoretical-empirical, partly analytically-oriented explanatory claim. The aim was to provide a comparative account of the structural changes in individual industrial societies that had occurred since the last quarter of the 19th century. The goal was to use the concept of organized capitalism as a periodization term, and to make explicit its viability for concrete historical situations with regard to the intertwined changes in economy and politics as well as in the area of collective ideas or ideologies. After the publication of the conference proceedings, Schieder – in 1972 still chairman of the German historians’ association – was very annoyed by a footnote in Wehler’s contribution which might have seemed somewhat mischievous (Nonn 2013, 337-338). The Bielefeld historian had claimed that the Association of Historians, during its annual congress in Regensburg, had shown little interest in the panel on organized capitalism. Despite the large number of participants, he said, the association had provided on hand far too few copies of the panel-related papers (up to 12 pages each). Wehler asked somewhat sarcastically whether this practice would also have been applied if the topics had been “Bismarck’s constitutional system as an organization of peace” or “Brüning’s successes in the struggle with the crisis” (Wehler 1974, 36-57). This remark was understood or misunderstood in the guild as an allusion to the programmatic preference of the Association of Historians for the history of events or political history and therefore indirectly as a personal attack on Schieder in his capacity as president of the Association. Wehler later learned from Theodor’s son Wolfgang that his father was utterly irritated by this remark. Thus, Wehler wrote a long letter to Theodor Schieder in which he apologized and reiterated that his remark was not an attack on his work as president of the Association. His apparently “misleading formulation” as to whether the “Association of Historians would have acted similarly to our working group on other issues” was not “an accusation of political censorship directed at you personally or meant as an allusion to the possibility of such censorship” [45]. He had only been annoyed, he said, by having experienced such a mishap with the Association for the second time, and an “informing telephone call” would have been sufficient for the panel papers to be printed in a timely manner and in sufficient numbers in Bielefeld.

In the meantime, however, Schieder had informed Werner Conze, Erich Angermann, Karl Otmar von Aretin, Karl Jordan, and Friedrich Vittinghoff, namely the former and the new members of the executive committee of the Association of Historians, about Wehler’s remark and suggested to them that they cannot remain unchallenged with regard to possible effects on the public, both domestically and abroad” [46]. At the same time, together with Angermann, he wrote down a statement from which it emerged that “the management of the Association treated all panels completely equally and correctly” [47]. On the one hand, the Association was not able from the outset to make a commitment to copy the thesis papers for all participants. On the other, such a working group as the one on “organized capitalism” could only have come about because the Association’s managing board would have made an effort to promote new research topics. The next day Schieder wrote to Wehler. In his reply, he accepted Wehler’s apology but once again clearly pointed out that the matter had “a significance that goes beyond the personal” [48]. What at first glance appeared to be a small matter for Wehler might in fact “seem like a tempest in a teapot” for Schieder [49]. Wehler’s statement could be understood as a kind of boycott by the younger cohort of historians in the Association of Historians against the representatives of the older historians: “Once again, the Association of Historians, which is unreceptive to everything new, and its leader have put new, young forces at a disadvantage! But was it not exactly the other way around? Didn’t I make Winkler’s working group possible in the first place by my resolute appearance, and don’t I deserve thanks for that? In the USA, for example, one would have to see everything exactly the other way around, if, as it is to be feared, your remarks are misunderstood” [50]. For this reason, he found Wehler’s suggestion to change the note in the second edition of the volume unacceptable: “I think it should just be deleted” [51]. In order to protect the reputation of the Association, Schieder informed his “former scholar” Wehler of the statement he had written on the matter, which was to appear first in a newsletter of the Association of Historians and then, in order to reach a wide audience, in the journals Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht and Historische Zeitschrift. This episode, which certainly may be marginal from a historiographical viewpoint, shows nevertheless how hypersensitive the historical field was in the early 1970s.

The field became increasingly differentiated in 1975 with the founding of the journal Geschichte und Gesellschaft. The idea of a new journal was already circulating in the second half of the 1960s. In the fall of 1967, Wehler had reported to Rosenberg about a meeting with Wolfgang Sauer, who had suggested founding a new journal that would stand out from the classical professional organs in terms of content and form. Although he had rejected cooperation with Sauer from the beginning, he summarized to Rosenberg the topics of discussion and therefore also his thoughts on a possible future journal, which “à la longue should have created an alternative to the HZ [Historische Zeitschrift] and its monopoly” [52]. Besides the need to find an editor, he wrote, “because of the accumulation of offices among a few people, such as Schieder, Conze, Erdmann, it would have to be run confidentially for the time being out of consideration for the younger man” [53]. In his opinion, given the general situation within the historian community, such a project could only meet with a positive response from young historians: “The oligarchs, who still have quite a good deal of autonomy over the chairs, will all react sourly because Schieder and Erdmann publish their own journals” [54]. At the same time, such a project should be run by “a younger man with courage, his own institute (since secretary and other help is indispensable at first), so for example by Bracher or Vierhaus” [55]. He concluded by pointing out that for such a project to be successful and accepted, it would be necessary for Rosenberg and Bracher to participate as well, “so that there would be a group left of center” [56]. A few years later, the project took shape through collaboration with Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. The founding group’s interests were clear: to publish a journal that would act as a point of distinction from any other history journals. Geschichte und Gesellschaft was to focus on a comprehensive idea of social history as a more general interpretation of society and its processes, that is, on the historical dimension of social life. When Wehler unsuccessfully sought funding for the journal from the Volkswagenwerk Foundation in 1974, he wrote in his application that the founding group wanted to fill a “perceived gap” among the older types of journals in terms of methodological guidelines, thematic emphases, and theoretical outlines [57]. The Historische Zeitschrift had “never favored our kind of social history”. Moreover, its “quasi-monopoly of publications in general history […] often led to a backlog of manuscripts that lasted for years” [58]. Other journals, such as the Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, would focus exclusively on the Nazi period while others, such as the Vierteljahrsschrift für Sozial-und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, “pursued conventional questions of the two disciplines without any discernible focus” [59]. As distinguishing features, Wehler emphasized interdisciplinarity, the study of processes and structures of social change, economic structures, and political forms of rule, a primary focus on problems in the wake of the so-called dual revolution (industrial revolution and political revolution), and a systematic linking of empirical analysis with approaches from the social sciences. Moreover, the project would employ a novel editorial concept of dedicating each issue (three to five articles) to a specific topic and a rigorous peer-review process; it would serve as a discussion forum and place of debate for controversial issues in historical scholarship; and it would be governed by an advisory board of renowned foreign historians (including David Landes, Timothy Mason, Arno J. Maier, Hans Rosenberg, and Eric Hobsbawm) as guarantors of high scholarly standards. Thus, it is evident how the editors sought to present the journal as a real innovation.

Lutz Raphael rightly pointed out that much of the announced programmatic orientation and innovative willingness was not realized in the end. The interdisciplinary claim was heavily diluted and the application of theoretical models was often detached from the empirical topic (Raphael 1999, 5-37). A national-centered perspective dominated the journal’s publications during the first 25 years of its existence. However, in analyzing the internal practices within the editorial board with regard to the choice of topics, the selection, and the review process of proposed contributions, but also with regard to the co-optation of new members on the editorial board, one is confronted with a multi-layered situation. These practices testify to an ongoing discourse that has been continuously reweighted by external and, in some cases, internal criticism, and has thus often led to reactions. This applies to the question of more interdisciplinarity, to the original idea of re-discussing modern German history beyond the narrower framework of national history, to the problem of a thematic focus of the first decade that was too fixed on the history of and controversy about the empire, and to the increased reception and discussions regarding the challenges of new historiographical turns [60]. There was, all things considered, no orthodoxy of positions. The editors were self-critical enough to realize that they should respond to new conceptual, programmatic, and intellectual impulses, but without blurring the guiding purposes of 1975, in order to be able to maintain its particular place in the competition of journals. Geschichte und Gesellschaft was originally not supposed to become a journal for generalists because, as its subtitle Zeitschrift für Historische Sozialwissenschaft suggests, it ultimately built on the distinctiveness of its approach.

V. What influence did the “teachers” have on young doctoral and postdoctoral scholars? Did a new generation of researchers arise from the foundation of the methodological and theoretical premises of a critical social history? To what extent did these scholars share and pursue the Bielefeld-specific academic program? To answer these questions, it is necessary to investigate the intergenerational transmission of research orientations. At the outset, however, it must be emphasized that two variables should always be taken into account in connection with such scholarly developments: on the one hand, academic or spatial mobility, which is a constitutive part of regular academic careers; on the other hand, the fact that the methodological-theoretical assumptions and approaches of every scientist are subject to constant change and rethinking over the course of time and can evolve according to the shift toward new research objects and mutating epistemological interests, so that the starting positions of earlier work rarely coincide with later positions.

These remarks also apply to the structural changes that affected the faculty between the late 1980s and the early 1990s. Some leading personalities from the Bielefeld circles had moved to other places or retired when they reached the age limit: in 1988, Jürgen Kocka moved to Berlin to the Free University and two years later Hans-Jürgen Puhle moved to the University of Frankfurt am Main. In 1988, Reinhart Koselleck became emeritus and was followed two years later by Sidney Pollard. Wehler continued to work in Bielefeld until his retirement in 1996; Peter Lundgreen followed in 2001. This generational change had an impact on the faculty’s programmatic vision. Some of the newly hired professors continued to practice a somewhat modified social history, while others preferred different research approaches in distance and demarcation from the past. Some young historians who had been trained in Bielefeld followed their “teachers” to their new working places, others found employment at universities away from Bielefeld after completing their doctorates, while some others eventually came from outside to do their doctorates or habilitation.

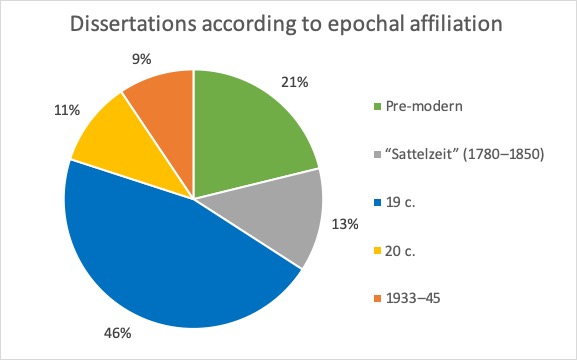

Against this mutating backdrop, quantitative data offer us indicative insights. In the first twenty years of its existence, i.e., until 1993, 85 PhD theses were submitted to the Faculty of History; by 2005, the number had risen to 210. Among these, 18 theses dealt with pre-modern topics, and this number grows by ten or eleven units if we count those doctoral theses that predominantly looked at the Sattelzeit (1780-1840/50). Overall, there were relatively few dissertations genuinely contributing to the history of the 20th century in general: a total of nine, integrated by a further eight which dealt with questions about the history of National Socialism. Thus, between 1975 and 1993, 46% of dissertations dealt with the long 19th century.

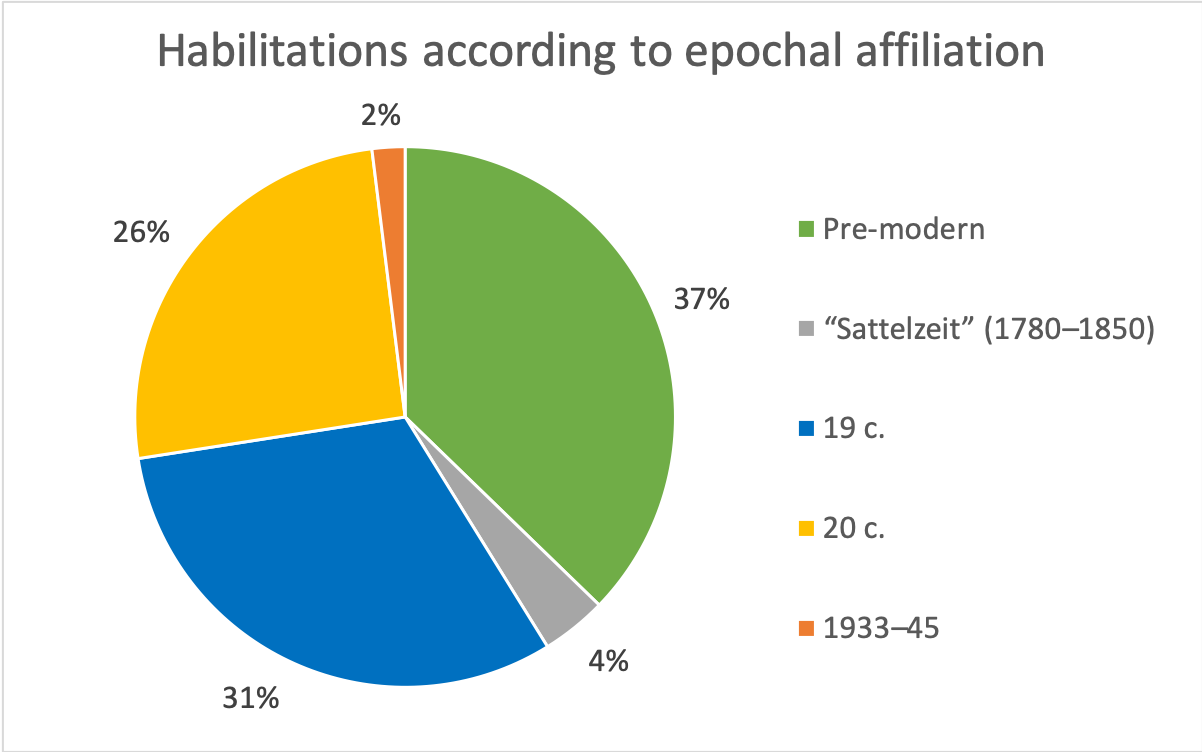

By 2004, a total of 51 habilitations had been successfully completed. Compared to the dissertations, the proportion of habilitation theses focused on the pre-modern period is higher. In any case, research on the 19th and 20th centuries predominates here as well. In addition, by 1999 there were a total of 21 scholars who received their doctorate in Bielefeld between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s and subsequently completed their habilitation there as well.

Reviewing contents and approaches of the dissertations on economic and social history of the 19th and 20th centuries, some interesting tendencies can be observed. First, the studies predominantly address classic fields: social groups and strata, the highly differentiated spectrum of bourgeois social formations, socio-economic and political developments in agrarian and urban areas or regions, workers’ and labor movement history, as well as the history of trade unions, entrepreneurial and industrial history, etc. Second, a shared feature consisted in the explicit recourse to theoretical references and explanatory models originating from a very wide disciplinary range, thus not exclusively oriented toward socio-theoretical or economic theories. In addition to modernization-theoretical interpretations (Schissler 1978; Kuhlemann 1992; Jessen 1991) and partly modernization-critical interpretations (Boch 1985), we see represented a wide range of industrialization theories, models on the connection between socio-economic developments and domestic and foreign politics (Müller-Link 1977), theorems of family sociology with respect to specific social groups in their historical context (Reif 1979), of social structural analysis (Ditt 1982), of professionalization theory (Huerkamp 1985), while the overall theoretical positions in PhD and habilitation monographs also included action-oriented (Mergel 1994), mentality, experience and everyday historical approaches (Daniel 1989; Frevert 1984). In other words, there is no lack of works that linked social history with political and institutional history, or that included the history of mentality, religion, and experience, and went as far as to consistently link structural history and Alltagsgeschichte.

Third, the new generation reflected the changes in the intellectual climate of those years and absorbed impulses from everyday history and cultural history into concrete research practice without fears of contact. They do not seem to have been particularly interested in polarizing different research positions, nor did they seek out confrontation; rather, they endeavored to operate with methodological-theoretical approaches that had hitherto remained peripheral to economic and social history. This could be done explicitly, as in Ute Daniel’s dissertation on women in wartime society. There, Daniel did not consider the dispute between historical social science and everyday history – as centered on the core question of where the “actual” core area of historical research could be found – to be of any further use. Instead, she pleaded in her research “to make the linking of experiential and structural history […] useful for historical women’s studies” (Daniel 1989, 13).

But even in the earlier dissertations from the 1970s, the tendency can be observed to treat the areas of economic and social history through aspects of cultural history on an empirical level. This applies, for example, to Josef Mooser’s dissertation on peasants and the lower classes in the area of the Prussian administrative district of Minden between 1780 and 1848 (Mooser 1984). As he wrote in the introduction, his main epistemological interest lay in the forms of social inequality in a rural society, the determinants of social stratification, the social relations between the classes, and the political behavior of the lower classes around 1848. In his analysis, he remained “committed to social history in a narrower sense […], i.e. the study of supra-individual, “objective” economic and social structures, the development and situation of classes and strata, their relations and conflicts, which is closely linked to economic history” (Mooser 1984, 22 f.). At the same time, he draws on a social-anthropological concept of “culture” as a class-specific everyday “way of life”, as “material culture”, in which knowledge, norms and symbols are indissolubly intertwined with the organization of material production. Differently from some narrower social history, the “subjective” experiences and the perceptions of social structures and processes are thereby investigated as “expressions” of social relations and relations of domination (Mooser 1984, 22).

For Heinz Reif, it was self-explanatory that without including the dimensions of religiosity, education, or lifestyle, it was difficult to grasp the transformation of the Catholic Westphalian nobility from a social estate (Stand) to a regional, social, and political elite in Prussia, i.e., to describe processes of accumulation and maintenance of political power as well as class formation and adaptation (Reif 1979).

Fourth, dissertations on systematic historical comparisons between countries were rather a rarity – a total of three until the early 1990s – although internal comparisons between cities and regions were a common practice in many works. Equally few works have explicitly taken a stand on the controversial thesis of a German Sonderweg in the modern era. In those few instances, it was linked to an epistemological interest in highlighting the causes of the conditions of the German modernization path; for example, in the case of the German trade unions, the fact that “trade unions, elementary drivers of the democratization of the economy and society, developed comparatively late in Germany” (Eisenberg 1986, 16). In other cases, the Sonderweg thesis was taken up in order to make clear, from a comparative perspective, the specific national historical conditions according to which the “influence of fascist and anti-Semitic movements in Britain failed in the ‘era of fascism’” – which at the same time implies a differentiation of the idea of a German Sonderweg (Bauerkämper 1991, 17 ff.). Finally, the Sonderweg thesis played a role in distinguishing the peculiarities of German white-collar culture (necessity of secularity, some “Standesleben” and “Standespolitik”, influence, prestige) in the interwar period from the peculiarities of the German pre-industrial, late-corporatist, bureaucratic tradition (Prinz 1986). The reference to the German Sonderweg was much more present in the qualifying works that were produced in the 1990s within the framework of the Collaborative Research Center (Sonderforschungsbereich, SFB) on the Bürgertum.

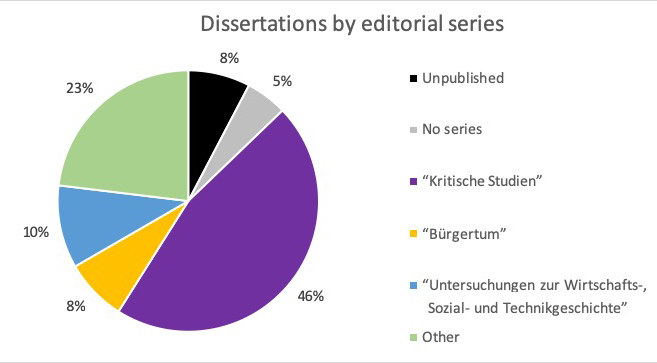

Fifth, and finally, more than half of the dissertations were published in the Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft Series. This can certainly be interpreted as a kind of symbolic commitment on the part of the emerging scholars to the methodologically open premises of historical social science, or at least it was understood that way by the “teachers”.

On the matter of intergenerational transfer, the assumption expressed several times in this essay and repeatedly emphasized by the protagonists themselves is essentially confirmed. Jürgen Kocka has always emphasized that the new social history of Bielefeld has not been averse, but rather open to dialogue with other research approaches. The fact that, then, this dialogue faltered toward the end of the 1980s, when social historians wanted to assert primacy of society over culture in research debates, was largely a reaction to the radical criticism in cultural history – a critique revolving around the social-historical preference for synthetic objectives and macro-historical explanatory models. The new cultural history, while trying to position itself within the historiographical field, presented its approach as an open alternative, an “opposition science”, to social history, but – so the viewpoint of the Bielefeld social historians would indicate – without clarifying the multifaceted concept of culture with the necessary precision. But that is another story which developed vividly along the exchange of two quite dialectical counterparts.

Despite minor individual nuances, the younger generation does not seem to have been particularly interested in positioning itself along these rapidly hardening frontlines within its research practice. Quite the contrary, the discussions about a reorientation of the historical sciences toward every-day or cultural history worked in instrumental terms as a beginning moment of the later push for a new social history, less imprinted on structural analysis. It was precisely these practices – which were often individual among the junior historians – that shaped a process of student formation. If the claim of the “teachers” was to establish social history as a history of whole societies and therefore precisely to make society the new subject of history, then the guiding theme of society was precisely the trait d’union between them and their “students”.

Conclusion

Sociological criteria of description with regard to the formation and consolidation of “academic schools” prove for a variety of reasons problematic and too blurred for the case of the Historische Sozialwissenschaft.

First of all, the perspective of a group-conformist style of thought misses the fact that there were differences and peculiarities among individual historians. Indeed, one can ask whether a Bielefeld “group” actually existed. Even if one concedes that it took time to build up the faculty, the image of excessive homogeneity is deceptive. We have only to remember, for example, that Klaus Hildebrand had been a faculty member in the 1970s (albeit for a very short time), and above all that Reinhart Koselleck and also some historians of pre-modern times can by no means be described per se as members of a “Bielefeld group” of the Historische Sozialwissenschaft. Still, to some extent, there were certainly intellectual ties, and in part there were certainly even personal ones. As important and significant as the cohesion effects of the programmatic and faculty-political power of Wehler and Kocka were, they sometimes provoked demarcation as well.

Thus, one should rather ask about basic commonalities and differences. In the Bielefeld faculty, a certain coherence of views can be observed which promoted cohesion. A few years ago, Jürgen Kocka rightly pointed this out in an interview: criticism (both in the sense of criticism of tradition to the subject and of social criticism), orientation toward theory, willingness to experiment, and turning to social history are considered by him to be the central dimensions of what can possibly be thought of as a “Bielefeld school” (Kocka 2014, 98). And one might add Westbindung as well to this list. All this stood for an innovative willingness and at the same time for the specificity of a location which very quickly became attractive to younger students from other universities at home and abroad. Nevertheless, this cannot all be subsumed under the rubric of style of thought, which in turn is attached to a collective of thought and almost dictates to the individual historian how he or she should understand and tell history. Moreover, this does not correspond to the self-understanding and positioning of many of the protagonists of the Bielefeld faculty. Instead, they have always emphasized that, despite a common thrust, there has been a “relatively high degree of heterogeneity” and, in part, competition (Kocka 2014, 97). Internally, Wehler recounted in an interview published in 2006, that “there was not the sense of school formation” and Koselleck had “always emphasized that he did not belong to it.” Instead, he had “pursued quite different interests and also did not see himself as the head of the school” (Wehler 2006, 89-90). By the way, Hans-Jürgen Puhle already referred to a heterogeneous structure in 1978 in his pointed criticism of all those historians who sweepingly “fashionably and cheaply” ascribed the label of the “Kehrites” and propagated the legend of the “Kehrsche Schule” (Puhle 1978, 108-119).

The institutional school concept can, with limitations and only for a certain phase, be of heuristic use also with regard to the external “members” from Bochum, Berlin, Giessen, Cologne, or elsewhere. Since the mid-1970s, the institutionalization process at Bielefeld University (personnel policy, research programs, curriculum, recruitment of young researchers, in-house journal and book series, etc.) was enforced and consistently carried out, and was of great importance for making the new shared scientific postulates visible in the German and international historical field. This process was part of the strategic action of a historical science that understood itself as Oppositionswissenschaft and began to generalize between the mid-1970s and the early 1980s, gaining increasing resonance and recognition within the framework of a national and international network that relied on background and close personal relationships.

At the same time, however, there is an important limitation to these observations. These processes did not take place on the basis of a unified and closed theory building, which in turn would be absolutely necessary for the constitution of a “scientific school”. The Bielefeld historians did not develop a meta-theory, a theory of history, if one disregards the Historik, the theoretical reflections on the conditions of human action in history and of thinking and writing about history by Reinhart Koselleck – who, however, was at best a Freigeist in the Bielefeld glasshouse of historical social science, not bound by the internal code (Hettling and Schieder 2021, 42-46). There was no homogeneous epistemological and theoretical center. Theory orientation à la Bielefeld meant above all looking at the systematic social sciences from the viewpoint of making pragmatic use of its models in the concrete research process (Koselleck, for example, was still against this attitude and, beyond this, his theoretical considerations went in different directions). It was the core subject of social-historical topics (class, social groups, industrial society, social inequality, work, etc.) that required the use of theory itself. In other words, one was not interested in the epistemological status of particular theories, but rather in their expedient use. For the narrow core of the Bielefeld historians, the complexity of historical phenomena required a variety of theoretical and methodological approaches that allowed for the integration of different aspects of real historical factors. An understanding was reached on situational or contextual historical theories with a limited scope, because “precisely to the extent that social-scientific theories lose their usually platitudinous ‘generality’, they gain in selectivity and meaningfulness” (Wehler 1973, 18). In Wehler’s words, every architectonics of abstraction “must remain connected by a kind of umbilical cord with empirical individual research and its patterns of interpretation” (Wehler 1980, 222). Similar to Jürgen Kocka, “more totality” could not be developed as a mere addition of different theoretical approaches, but rather within the framework of overarching theories that can integrate those partial approaches and insights (Kocka 1981, 7-27). In its programmatic efforts to overcome social history as a narrowly thematically defined sub-discipline and then to tackle a more general interpretation of society and its processes, the Bielefeld faculty kept the field of social history open to a variety of theoretical and methodological suggestions, basic assumptions, and perspectives.

Here, in addition to professionalization, lay possibly the strong attraction for younger prospective historians. The effect on the new generation did not result from a methodological-theoretical fixed teaching, but rather from the openness and connectivity of a programmatic framework with all its political implications. Younger scholars, at least since the 1980s, increasingly took up these impulses from outside and tried to integrate further approaches, but in most cases without disenchanting the programmatic intention of the “teachers”. The term “school” is too narrow to describe this process; even as a metaphor, the term suggests the idea of a greater internal homogeneity, which never existed. Alternatively, it might be worth considering whether the concept of a specific “academic milieu” might not be more meaningful and analytically illuminating. Most likely, this would have greater heuristic utility than the “school” concept in describing the particular academic milieu in Bielefeld, which lasted from the 1970s to the 1990s. Among the constituting factors was, first, and of no little importance, the personal constellation and the personal impact of the two main protagonists, Wehler and Kocka, who harmonized closely with each other despite minor incongruencies and promoted the climate within Bielefeld precisely through a constructive divergence with Koselleck. Only the association of the two made the Bielefeld social history something different and new – as symbolized in the Friday Colloquium, which both led together for 15 years. Second, there was a special understanding of theory, which did not rely on common paradigms, but functioned more as a framework program with osmotic boundaries. Third, there was a special effect of common themes (society, the Sonderweg), which were especially formative for the historians of modern history and for which one could almost speak of guiding themes rather than a guiding theory. Fourth, there is an identifiable political-pedagogical impetus. Fifth, and finally, there was an opening to the social sciences and later – also in minor terms among the older ones – to cultural studies.

Bibliography and Sources

Abbreviations

- UABI Universitätsarchiv Bielefeld

- UniBi Universität Bielefeld

- BArch Bundesarchiv Koblenz

- UA St. Louis St. Louis University Archives

- Archive Collections

- Nachlass Hans-Ulrich Wehler

- Nachlass Theodor Schieder