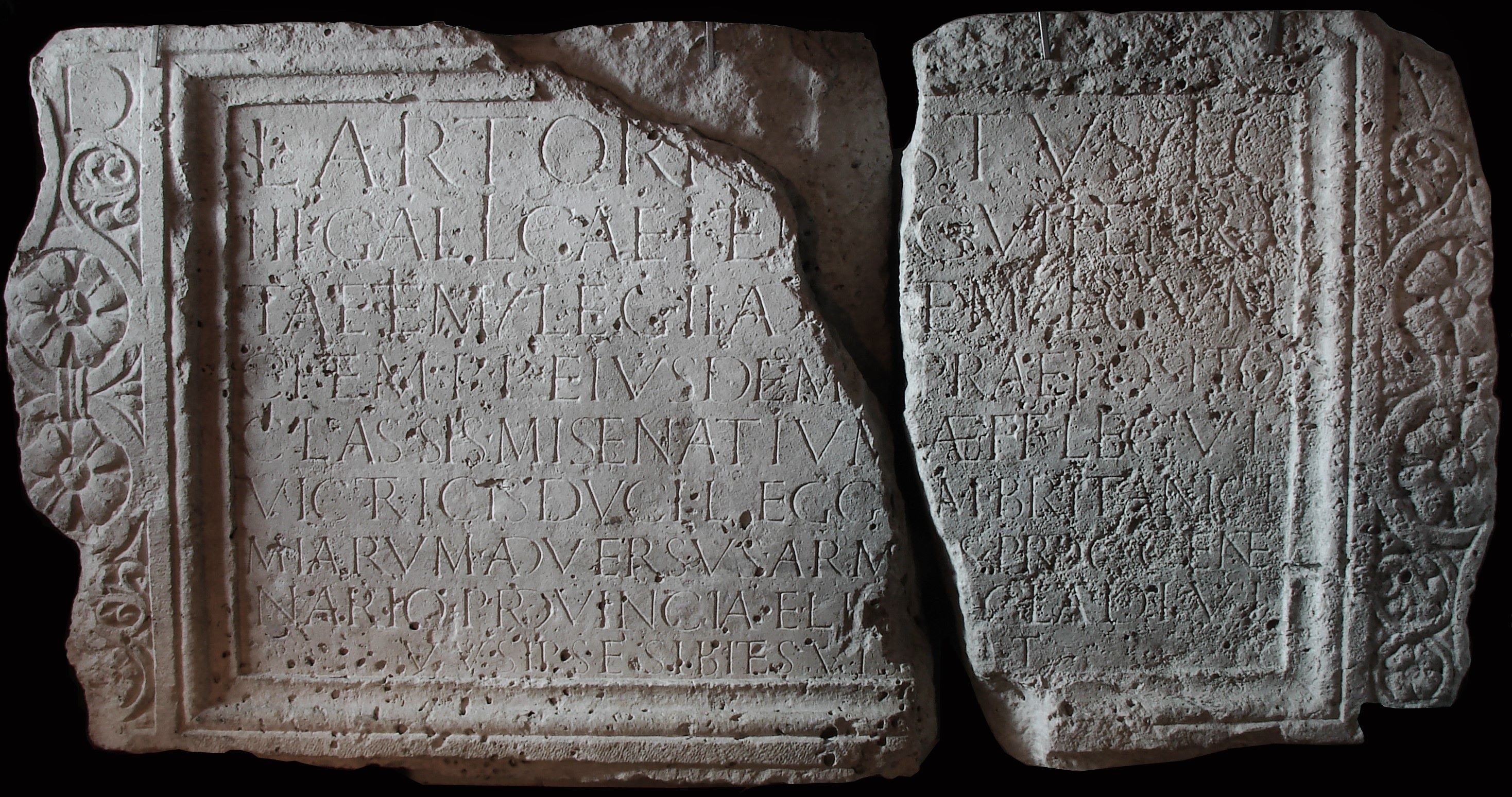

Provincia LIB(urnia) is mentioned only once in sources, in the larger of the two sepulchral inscriptions of Lucius Artorius Castus, from Podstrana, in the area of the Roman Salona. The larger inscription, broken in two pieces (CIL 3, 1919=8513=12813), was once embedded into a mausoleum (Fig. 1). The other represents a small fragment, a remnant from Artorius’ sarcophagus with strigils (CIL 3, 12791=14224; Cambi 2014, 33-36) (Fig. 2). According to Huskinson (2015, 26), the continuous production of sarcophagi with strigils, with the exception of isolated examples from the first century, begins around the years 120/130 and continues until the early fifth century. In this paper, we propose the reconstruction of the life and career progression of Lucius Artorius Castus, which will enable us in turn to propose that the province of Liburnia had been established at the time of the Marcus Aurelius’ Germanic wars.

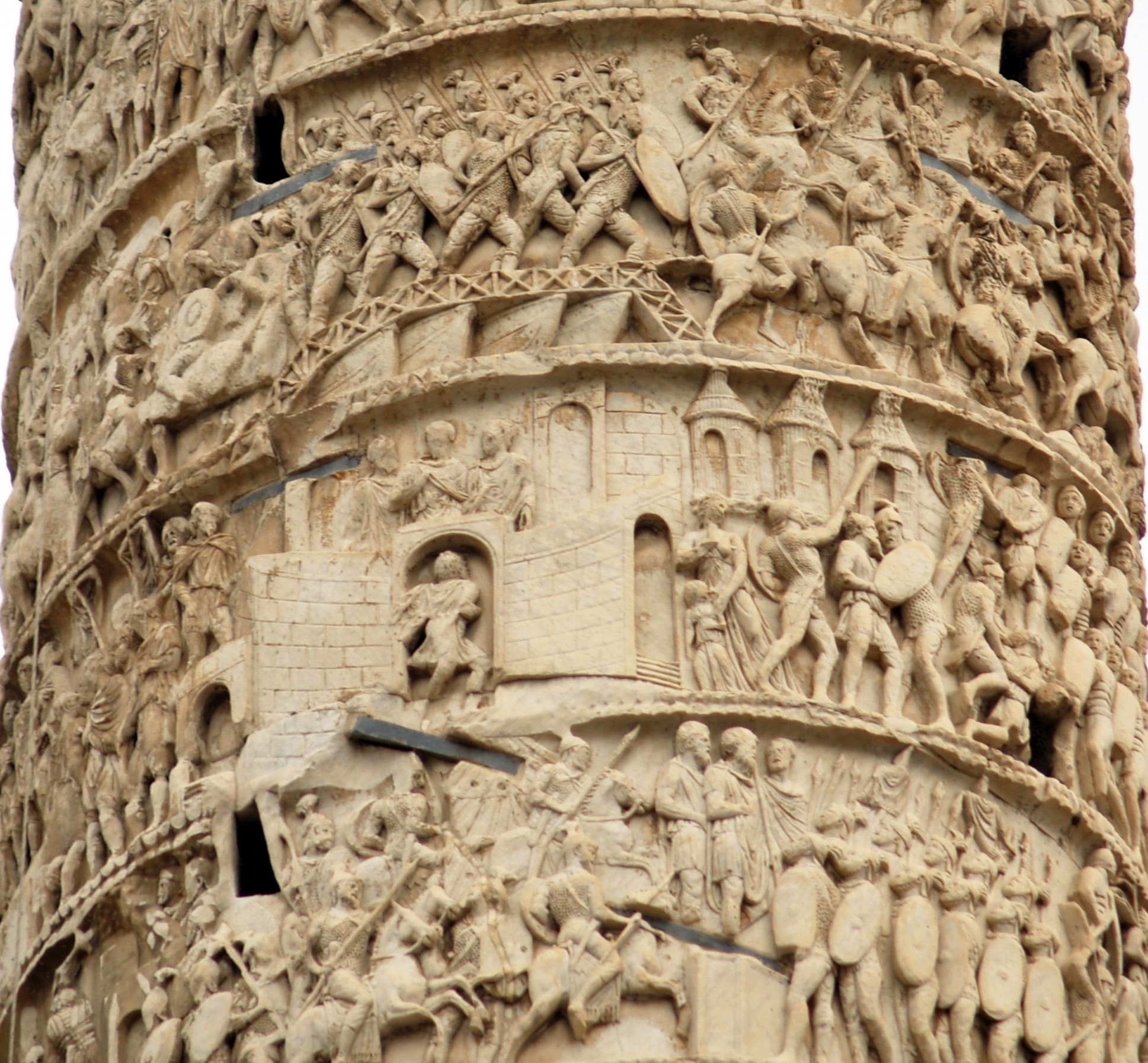

The peaceful reign of Antoninus Pius, interrupted by only minor disturbances in Mauretania, Judea, and Britain, proved to be the key period in the temporal and spatial fixation of Artorius’ career (Birley 2000, 149-155). The two final specific positions mentioned on the larger inscription, those of dux and procurator provinciae, could have been attained by Artoriusonly during a war-related crisis, when the established social frameworks bend and the borders between various layers are more easily passable, so that the extraordinary elevation of personal status, and the ad hoc promotion to higher and exceptional positions are more likely. For him, the era of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius represented such a moment, when, as early as the first year of his reign, unrest broke out in the East and the war with the Parthians began (Birley 2001, 121). With the Parthian war still going on, the pressure of the Germans on the Northern borders culminated in their crossing of the Danube, and this incursion into the Roman territory turning into a protracted war. Unfortunately, a potentially key historical source for that period, the columna centenaria Divorum Marci et Faustinae, is currently of limited use for the interpretation of expeditiones Germanicae, due to the unresolved identification of numerous events, chronological problems, and the anachronism of some scenes (Birley 2001, 149, 163-178, 206-208; Birley 2002, 505-506; Birley 2012, 226; McLynn 2009, 323-324; Kovács 2009, 155-180).

The itinerary of Artorius’ journey through the provinces and cursus honorum was reconstructed on the basis of the itinerary of the legions and units in which he served, the historical framework, the hierarchy of social strata and groups, and the promotional path from the third citizen class to the equestrian ordo during the 2nd century (Miletić 2014, 112-126). Artorius’ participantion in major war events is indicated by his command over vexillations that are widely used on battle sites in the period from Marcus Aurelius to Septimius Severus (Saxer 1967, 33-49 no. 63-88; Ibeji 1991, 156-157; Cowan and McBride 2003, 17-19). This is confirmed by his military title of dux, frequent only from the period of Emperor Septimius Severus (Saxer 1967, 44 no. 77 i 78, 48 no. 86-88, 57 no. 107; Ibeji 1991, 226-234). The inscription CIL 3, 1919=8513=12813 after the first decades of the 2nd century is out of the question due to the absence of characteristic late epithets in the names of the mentioned units, due to the paleography of the letters and epigraphic peculiarities of the inscription as well as the existence of a some procuratorial province mentioned on the Artorius inscription CIL 3, 1919=8513=12813. Only the first three letters LIB remain from the name of the province, and governor Artorius ruled it with the power of ius gladii.

Although promotions of centurions are observed through individual cases, they are also determined by large-scale processes, for example, the need to replenish the troops due to losses in wars, or mass dismissals from military service. Artorius probably became a centurion while Legion III Gallica was stationed in Judea in Hadrian’s time, promoted after thirteen to twenty years of military service, a common time-span for progression through military and non-commissioned officer positions (Ritterling 1925, 1521-1524; Breeze 1974, 442). Under Emperor Hadrian, the newly made centurions were experienced soldiers about thirty years old, and “vitis was given only to those who were hardy and in good standing” (HA, Hadrian 10, 6).

The legion was stationed in Syria when Emperor Hadrian was on a journey to the East in an atmosphere of deteriorating Roman-Jewish relations, intensified by the decreed start of the construction work in the new Jerusalem – Aelia Capitolina (Sicker 2001, 180-184; Goodman 2008, 483-488; Bloom 2010, 202-203). The Bar-Kohba uprising lasted from 132-136, and the Emperor, due to the loss of legions and of the control over the territory, sent from Britain to Judea/Syria Palestina his best generals to solve the problem, with Gneus Minicius Faustinus Sextus Iulius Severus as the one leading among them, He was a native of the colony of Aequum in the province of Dalmatia, and young Artorius’ countryman (Cass. Dio, LXIX 13.2 – 14.3; CIL 3, 2830; AE 1904, 9; Bulić 1903, 125 = AE 1904, 9; Abramić 1950, 237-239 = AE 1950, 45; Gabričević 1953, 257-258; Eck 2003, 158-160; Birley 2005, 129-132). At that time, Artorius’ superior knightly military tribune – tribunus militum angusticlavius – was Statius Priscus, also Dalmatian. Later on, Prisco is to achieve a remarkable progress and become a senator as homo novus (CIL 3, 1523; Alföldy 1976, 294).

Artorius achieved his next posting as a centurion in Bostra, with the Legion VI Ferrata (Ritterling 1925, 1587-1596; Miletić 2014, 114). To summarize his progress as we propose it, the first two centurion positions, of a 3-to-5-year tenure, were held by Artorius in the Judeo-Nabataean area, and his commanders were Dalmatians. Artorius was transferred to his new posting as a centurion in the Secod Legion Adiutrix to Aquincum in Pannonia on the Danube Limes, and then, in the forties of the second century he became a centurion in the Fifth Macedonian Legion in Tresmis in Moesia Inferior, near the confluence of the Danube and the Black Sea (CIL 3, 14347; Ritterling 1925, 1446-1449 and 1576-1577; Visy 1988, 81). A contemporary of Artorius, centurion Tiberius Claudius Ulpianus, was also transferred to the Fifth Legion from the Second Legion Adiutrix in Aquincum, and had previously served in Syria in the Tenth Legion Fretensis, which was part of the local garrison when the Bar Kokhba revolt broke out (CIL 3, 6186; Mor 2016, 289; Matei-Popescu 2010, 61).

In Fifth Macedonian Legion, Lucius Artorius Castus, in his fifties, became the primus pilus, by virtue of the vast military experience he shared with most others of his rank. This was followed by an honorable discharge. The discharged primipilares received a significant grant of money, which qualified them to progress from the third citizen class into the equestrians (Suetonius, Caligula, 44; Dobson 1974, 376). To achieve such a remarkable success, demonstrating military virtues was necessary, but the support of the commander and governor of the province were also indespensable.

The inscription indicates that the next position held by Artorius, now an eqestrian, was probably around 152-154 at the elite Praetorian fleet at Misenum on the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy (Miletić 2014, 115, 126). The rank of praepositus classis praetoriae Misenensium corresponded to the positions in the militiae held by young hereditary knights, or to the praetorian tribune in Rome. It is an enigmatic assignment: for Artorius, it represented an intermezzo before his assumption of a more usual and expected command post for primipilares: praefectus (castrorum) legionis with the Sixth legion Victrix in Britain. Gnaeus Julius Verus, who was the governor of the province at that time, from about 154/5 to 158, hailed from the colony of Aequum in Dalmatia. He was probably the nephew of Gnaeus Julius Severus, victorious in the Judean War, in which young Lucius Artorius also participated as a centurion (CIL 3, 2732 = CIL 3, 8714; RIB 1322; Speidel 1987, 233-237; Birley 2005, 145-149; Zaninović 2011, 507).

Artorius, instead of retiring, as was usual after having served as praefectus castrorum, continues his career in an unexpected direction, thanks to the next governor of Britain, Marcus Statius Priscus, speculated to also have been of a Dalmatian origin by Birley (2005, 151-155). He is likely to have served as a tribune in Artorius’ unit during the Judean War, and later became a successful senator and completed the full cursus honorum. Priscus went from Britain to the East in 162, to replace the deceased governor of Cappadocia (CIL 6, 1523; SHA, Marcus, 9.1; SHA, Verus, 7.1; Birley 2000, 160-164). We believe that Artorius was with him.

The two interruptions in the inscription CIL 3, 1919 = 8513 = 12813 caused a lengthy dispute on the exact troups and locations the dux Artorius commanded. We hereby summarize it by stating that the war in question was fought in the East between the Romans and the Parthians over Armenia. The fact that in the first published lesson Carrara saw the letter E in the word ARME[nio]S on the inscription from Podstrana is decisive for such a determination (Carrara 1852, 23, no. IX; Gwinn 2013). Among several posible identifications of troops he led we would settle for: dux legionariorum et auxiliorum Brittanicorum adversus Armenios. This solution is based on a syntagm in the inscription CIL 6, 1377, of his contemporary Marcus Claudius Fronto, which refers precisely to the Roman-Parthian War of 161-166. Artorius’ title dux which appears, albeit rarely, before the beginning of the 2nd century, should be understood in the sense of praepositus or praefectus or tribunus vexillationum – commander of vexillations. They are the main way of organizing troops in the Parthian and German wars under the emperors Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, and were commanded by senators and occasionally by knights (Saxer 1967, 44 no 77 and 78, 48 no 86-88, 57 no 107, 62 no 22).

At first glance, it seems contradictory that auxiliae bear the provincial name of “British”, or the ethnic name of the Britons, although sources for the Parthian War mention by name only the legions from the Rhine and especially from the Danube Limes, as well as vexillations from Pannonia (CIL 6, 1377; CIL 8, 7050; CIL 8, 18893; CIL 3, 7505; SHA, Marcus 8.6; Birley 2001, 123). Bearing in mind that it is common practice for auxiliary satellite units to accompany the parent legions, and that just before the war began, more than half of the ala, cohorts and irregular units from all over the Empire called Brittanica or Brittonum were stationed in Dacia, and the rest were on the Danubian limes in Rhaetia, Pannonia and Moesia, and one outside those areas, in Mauritania, it is clear from where the troops commanded by dux Artorius were tranferred from (Spaul 1994, 68-69, 72; Spaul 2000, 193-199, 201-203; Matei-Popescu and Tentea 2006, 131, 133, 135, 140; Campbell 2009, 15). These assumptions fit perfectly with the information conveyed by Historia Augusta, that the northern borders were deliberately weakened by transferring troops to the East due to the crisis with the Parthians (SHA, Marcus 12,13; Birley 2001, 123).

The Parthian and then the Germanic wars marked Artorius’ late-life career. The last of his listed functions, the equestrian procuratorial governor of the province, who possessed the ius gladii, is primarily of military nature and, we are convinced, could have been achieved exclusively in the context of the Alpine-Pannonian-Adriatic war theatreduring the Wars with the Germans.

Apart from the general trend of assigning equal importance to knights and senators in the military field, the rise of the military role of knights is the consequence of the acute shortage of high military commanders due to a prolonged epidemic of a serious infectious disease brought on by troops returning from the East. Lucius Verus, co-ruler of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, died of the plague during the German wars, in the winter of 168/169. His funeral was held in i the beginning of AD 169 (SHA, Marcus 18.1-8 and 20.1-5).

This was the time of the intensive fortification of cities, and the restoration and construction of camps, forts and ramparts in the wide Italian, Rhaetian-Noric and Illyricum areas, as illustrated on the column of Marcus Aurelius (Thill 2018, 291-298) (Fig. 3). The emperor’s goal was to protect Italy and Illyricum: “omnia, quae ad munimen Italiae atquuae Illyrici pertinebant” (SHA, Marcus, 14, 6; Zaccaria 2002, 77). Detachments of new units raised around AD 166 (legions Second and Third Italica, as well as First and Second cohors milliaria Delmatarum) participated in 169/170 CE in the effort to reinforce the northern walls of the Salona’s suburbia (CIL 3, 1979; CIL 3, 6374 = 8655; CIL 3, 1980 and its duplicate CIL 3, 8570; Cesarik and Glavaš 2017, 210). As the capital of the province of Dalmatia, it represented a potential target for German siege hence the army’s involvement in the construction works.

The building inscription CIL 3, 11675 from the year 168, naming the co-emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, was erected in Atrans on the Trojan Pass in Slovenia, a key point on the border between Italy and Norik on the so-called Amber Road that led from Aquileia to Carnuntum and Vindobona on the Pannonian Limes (Šašel 1954, 205; Šašel 1992, 231-233). The legionary camp at Ločica near Celea in Noricum had a similar defensive role, and was built by the Second legion Italica no later than year 175 (CIL 3, 5757,1g; CIL 3, 5757,4; CIL 3, 14369,2a-k; CIL 3, 14369,21; Alföldy 1974, 154-155; Winkler 1977, 224-225). Same unit built a fortress at Albing on the Danube (Bishop 2012, 46-47) from where it moved to the permanent camp at Lauriacum, completed in Commodus’ time, judging by the inscription CIL 3, 15208, dated September 18, 191 (Ritterling 1925, 1469-1470; Alföldy 1974, 165-167). An inscription from the legionary camp of Castra Regina in Regensburg states that in 179 AD, under emperors Antoninus Pius and Commodus, the Third legion Italica built a vallum cum portis et turribus (CIL 3, 11965). The intensity of construction work in the war zone is illustrated by over thirty marching temporary camps discovered north of the Danube (Fisher 2012, 39; Komoróczy et al. 2020, 177-254).

The inscription from Thibilis (Numidia) AE 1893, 88 of Quintus Antistus Adventus gave us direct confirmation of the existence of the military area Praetentura Italiae et Alpium in the time of Marcus Aurelius (Šašel 1974, 225-227). During the German War, after 168, Antistius was legatus Augusti at praetenturam Italiae et Alpium expeditione Germanica – commander of that sector consisting of a series of defensive walls and fortifications (Petru and Šašel 1971; Birley 2001, 251; Kovács 2009, 191ff.). Previously, like Artorius, he had participated in the Parthian war.

We assume that the command headquarters was the principia in Tarsatica (today’s Rijeka/Fiume) in the Liburnian part of the province of Dalmatia (Fig. 4). In a recent monograph, construction of the principia is dated, using the so-called small archaeological artefacts, to the middle of the 3rd century (Višnjić 2009, 62), and, accordingly Bekić (2009, 221) and Kos (2012, 287), between 260 and 270, or from 270-280, respectively (Višnjić 2020, 75). Most of the material found, as well as the first major concentration of coins, indeed originate from that period and testify to the dynamics of living in principia. In almost every category of finds, however, there are objects that can undoubtedly be dated in the 2nd century, and even earlier. For example: Hayes 10 terra sigilatta bowl, Africana 2a amphorae, Dressel 2-4 amphorae, Dressel 30 and Pompei VII amphorae, Aucissa fibulae, 1st-2nd century profiled fibulae, 1st-2nd century enameled plate fibulae, pendant for horse equipment Bishop 3C, some forms of glass cups, glass semicircular bowl, glass plates, spherical glass jug etc. (Percan 2009, 75; Višnjić 2009a, 125-132; Višnjić 2009b, 156-152; Janeš 2009, 231-235). The number and variety of these earlier artifacts are difficult to explain by the longevity of use if the building has not yet been built. In the monograph on the claustra Alpium Iuliarum, written by a number of authors, Kusetič (2020, 30) summarizes the chronology of the construction of buildings n [and?] that fortification system primarily on the basis of “numismatic finds that offer the bulk of the data” because “small archaeological material (artefacts) is chronologically problematic”. Coin evidence indicates that the edifices on the Claustra were erected in the late third century or later. There are, however, records of the stay of the Roman army in earlier periods. In the old town core of Ajdovščina (Fluvio Frigido, Castra) for example, artefacts from the end of the third to the end of the fourth century dominate, but among the earlier Roman small finds many metal artefacts were belonging to military garb and horse equipment, “which point to the presence of a military unit prior to the erection of the fortification” (Urek 2020, 374). Therefore, we stand by our opinion that the dating of construction of the principia in Tarsatica should be brought back to the 2nd century, during the German wars, as a part of intensive construction activities in the Alps-Danube-Adriatic region. We propose that the principia served as Artorius’ command post in the province of Liburnia.

At the end of the Germanic wars, emperor Commodus erected a series of castles (burgi and praesidia) along the Danube River in Pannonia Inferior in order to suppress the wandering Iazyges bandits (latrunculi), as evidenced by multiplied inscriptions with the same text from the Intercissa and elsewhere, dated 182/3 to 185 (Mocsy 1974, 196-197 fig. 196; Kovács 2009, 263; Kienast 2004, 149; CIL 3, 10312; CIL 3, 10313; RIU-05, 1127; RIU-05, 1128; RIU-05, 1129; RIU-05, 1130; RIU-06, 1426…). These events coincide with the overthrow of the praetorian prefect Sex. Tigidius Perennis, who tried to raise a rebellion against emperor Commodus with help of legions of Lucius Cornelius Felix Plotianus, legatus Pannoniae inferioris (Łuć 2020, 79-80). Pflaum, Wilkes, Šašel and Medini believe that these events triggered the separation of the province of Liburnia from Dalmatia (Medini 1980, 373-374). We consider that separation took place more than a decade earlier, as part of the general reorganization of the provinces on the northern borders of the empire during Marcommanic Wars, when various military areas (praetenturae) also existed in parallel. Therefore, the province of Liburnia would have been created immediately after the end of the Parthian War, at the time of the acute German crisis, around the year 168 when Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus crossed the Alps (Birley 2012, 222-223).

During the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, the status of the provinces in the entire region (Dacia, Raetia, Noricum and Liburnia) has been revised. A series of events preceding, or taking place in the early phases of the ongoing Marcomannic wars, including barbarian incursions into the Dacian aurariae, then the death of L. Calpurnius Proculus pretorian legate of Dacia Superior, resulted in the establishment of the Tres Daciae in 169-170 under the sole governorship of M. Claudius Fronto. (CIL 3, 1457; CIL 6, 41142; Wade 1969, 107; Piso 1993, 82-102; Birley 2001, 160; Birley 2012, 223-224). It is worth mentioning that Fronto had previously been decorated for his services in the bellum Armeniacum et Parthicum. Fronto’s procurator ducenarius in the same provinces was an equestrian, the future emperor Pertinax (AE 1963, 52). Pertinax’s service is related to the war milieu, so we assume that Artorius, with the salary and hierarchical class of centenarii, served as the governor of the small province of Liburnia ad hoc separated from Dalmatia in wartime circumstances. Raetia and Noricum, until the German invasion, were provinces under the administration of equestrian procurators. Due to the presence of a large number of troops (especially the legiones II and III Italica), after year 170 and the latest in 175, they changed their status to imperial provinces, each under the administration of a senate pro-praetorial legate. After that change, there were still procurators in Noricum, but financially with the rank of sexagenarii or centenarii, no longer praesidial (Alföldy 1974, 164; Hainzmann 1991, 62).

In the 2nd century, it became possible for a praefectus castrorum to advance to the position of centenary procuratorship, previously held by hereditary knights exclusively (Dobson 1974, 402). In the inscription from Podstrana at the end of the cursus honorum, Lucius Artorius Castus is listed as the procurator of a province, the name of which is preserved in the initials of LIB. We conclude that the province in question Liburnia, which previously represented a region in the western part of the province of Dalmatia. We exclude the possibility that the Latin term province was used here to denote the area of activity of the financial procurator. Instead, we posit that it was indeed an administrative and government unit separated from Dalmatia, managed by a presidial procurator. Namely, the creation of a new province and the fact that the equestrian Artorius possessed the ius gladii for the purpose of governance, can only be linked to the war zone in the area between the Danube and the Adriatic during the expeditio Germanica.

Ius gladii is an imperium power held by the highest senate magistrates. Such a magistrate has the ultimate authority in the province, which includes the right to command the army, punish and condemn to death. This power is held by praetorii and consularii in the position of military commanders (Liebs 1981, 218). It is emphasized in the inscriptions from Podstrana, as is in the case of Julius Pompilius Piso, who commanded two legions and associated auxiliaries during the German Wars and received the ius gladii: praepositus legionibus I Italicae et IIII Flaviae cum omnibus copiis auxiliorum dato iure gladii (ILS-1, 1111; Campbell 2009, 31). The reason why knight Artorius was given such great authority must stem from the fact that he was in command of military forces, a duty integrated into his procuratorial governorship position over the province of Liburnia during an acute war-related crisis. Artorius’ knightly career did not end with a procuratorship of the highest rank (ducenarius or trecenarius). As a non-hereditary knight, he was simply not eligible, but his last two duties were quite remarkable and extraordinary, a high military command.

It is important to note that the name of military area Praetentura Italiae et Alpium, formed during the Germanic wars, carries a geographical description, and does not coincide with the borders of Italy and the provinces, nor does it negate them. Lujo Margetić, on the trail of Šašel’s argument, proved that at the time of the formation of the Praetentura Italiae et Alpium, the borders of Italy did not move to the territory of Liburnia (Margetić 1990, 27-28). We do not know the dimensions of the province, but it is plausible to assume that they correspond to the dimensions of the historical territory of Liburnia from the river Raša – Arsia flumen to Krka – Titius flumen, that it corresponds to the area of Pliny’s (NH III, 139-141) Liburnian conventus juridicus Liburnorum with its center in Scardona (Demicheli 2015, 96-104). North of Liburnia, within the borders of Italy, is the main natural transit channel from Italy to Pannonia, under plateau Nanos (Roman Ocra), through the Postojna Gate (Fig. 5).

Based on the finding of a boundary stone with the inscription Finis // Aquileien/sium // Emonen/sium in the village of Bevke, M. Šašel Kos agrees with Jaroslav Šašel’s opinions that Emona and its Basin belonged to Cisalpina at least since Caesar’s proconsulate onwards. Consequently, the upper stream of the river Kupa (Colapis flumen) would delimit the territory of the colony of Julia Emona in Italia from Liburnia (Šašel 1992, 574; Šašel Kos 2002, 377). The Principium of Tarsatica and the initial lines of the fortification walls within the area of the praetentura are located in the extreme northern part of the newly formed province of Liburnia and extend further north into Italy. It is unlikely that the praetentura was dissolved in the early seventies of the 2nd century, because there came a time of fierce conflicts with Marcomanni, Quadi, Cotini, Hermunduri, Iazyges and other peoples, prompting Marcus Aurelius to ultimately undertake a second German expedition (Birley 2012, 229-230; Kovács 2009, 232-242).

Perhaps it was the death of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus’ withdrawal from further war that meant the end of Liburnia’s existence and its annexation to the mother province of Dalmatia. The province of Liburnia was not long-lived as we may say due to the lack of evidence, ex silentio. We do not know whether Lucius Artorius Castus, who after some fifty years of service at the age of about 70 years retired to the peace of his estate in Salona, outlived the province of Liburnia. For the same reason, any consideration of the borders of that short-lived creation is highly speculative and boils down to a comparison with historical Liburnia, as a part of Illyricum.

Abbreviations

- AE = L’Année épigraphique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. http://www.jstor.org/journal/anneepig.

- CIL 3 = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Inscriptiones Asiae provinciarum Europae Graecarum Illyrici latinae. Consilio et auctoritate Academiae litterarum Regiae Borussicae edidit Theodorus Mommsen. Berolini: apud Georgium Reimerum. Ab anno 1873.

- CIL 6 = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Inscriptiones urbis Romae latinae. Consilio et auctoritate Academiae litterarum Regiae Borussicae collegerunt Guilelmus Henzen et Iohannes Baptista de Rossi ediderunt Eugenius Birmann et Guilelmus Henzen. Berolini: apud Georgium Reimerum. Ab anno 1876.

- CIL 8 = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Inscriptiones Africae latinae. Consilio et auctoritate Academiae litterarum Regiae Borussicae collegit Gustavus Wilmanns. Berolini: apud Georgium Reimerum. Ab anno 1881.

- ILS-1 = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae, edidit Hermannus Dessau. Vol. I. Berolini: apud Weidmanos. 1892.

- PWRE = August Pauly, Georg Wissowa et al. Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler. 1894-1978.

- RIB = Collingwood, Robin George, and Richard Pearson Wright. 1965. Inscriptions on Stone. Vol. I of The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- RIU-05 = Die römischen Inschriften Ungarns: (RIU) 5. Intercisa. Von Jenő Fitz. Budapest-Bonn: Enciklopédia Kiadó – Habelt. 1991.

- RIU-06 = Die römischen Inschriften Ungarns. (RIU) 5. Das Territorium von Aquincum, die Civitas Eraviscorum und die Limesstrecke Matrica-Annamatia und das Territorium von Gorsium. Von Jenő Fitz, András Mócsy u. Sándor Soproni. Budapest-Bonn: Enciklopédia Kiadó – Habelt. 2001.

Bibliography

- Abramić, Mihovil. 1950. “Dva historijska zapisa iz antikne Dalmacije.” Ephemeridis instituti archaeologici Bulgarici 16: 235-240.

- Alföldy, Géza. 1974. Noricum. London-Boston: Routledge.

- –, 1976. “Consuls and Consulares under the Antonines: Prosopography and History.” Ancient Society 7: 263-299.

- Bekavac, Silvia, and Ivo Glavaš. 2011. “The Atilii in Asseria.” Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 28: 123-132.

- Bekić, Luka. 2009. “Antički numizmatički nalazi.” In Tarsatički principij. Kasnoantičko vojno zapovjedništvo, edited by Nikolina Radić Štivić and Luka Bekić, 185-225. Rijeka: Grad Rijeka.

- Birley, Anthony. R. 2000. “Hadrian to the Antonines.” In The High Empire, A.D. 70-192. Vol. 2.XI of The Cambridge Ancient History, edited by Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey and Dominic Rathbone, 132-194. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –, 2001. Marcus Aurelius. A Biography. New York: Routledge.

- –, 2002. “John Scheid et Valérie Huet (Éd.), Autour de la Colonne Aurélienne. Geste et image sur la colonne de Marc Aurèle à Rome, Turnhout, Brepols, 2000. 1 vol. 15,5x24 cm, 288 p., 176 fig. (Bibliothèque de l’École des Hautes Études, Sciences religieuses, 108).” L’antiquite Classique 71: 504-506.

- –, 2005. The Roman Government of Britain. Oxford: University Press.

- –, R. 2012. “The Wars and Revolts.” In A Companion to Marcus Aurelius, edited by Marcel van Ackeren, 217-233. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Bishop, Mike C. 2012. Handbook to Roman Legionary Fortresses. Barnsley: Pen & Sword.

- Bloom, James J. 2010. The Jewish Revolts against Rome. Jefferson-London: McFarland & Company.

- Breeze, David J. 1974. “The Career Structure below the Centurionate during the Principate.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. Vol. II.1, edited by Hildegerd Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, 435-451. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Bulić, Frane. 1903. “Cenni sulla strada romana da Salona alla Colonia Claudia Aequum (Čitluk presso Sinj) e sue diramazioni.” Bullettino di archaeologia e storia Dalmata 26: 113-126.

- Cambi, Nenad. 2014. “Lucije Artorije Kast: njegovi grobišni areal i sarkofag u Podstrani (Sv. Martin) kod Splita.” In Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend. Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30th of March to 2nd of April 2012, edited by Nenad Cambi and John Matthews, 29-40. Split-Podstrana: Književni krug Split.

- Campbell, Duncan B. 2009. Roman Auxiliary Forts 27 BC-AD 378. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- Carrara, Francesco. 1852. De’ scavi di Salona nel 1850. Prag: Haase.

- Cesarik, Nikola and Ivo Glavaš. 2017. “Cohortes I et II milliaria Delmatarum.” In Illyrica Antiqua II - In honorem Duje Rendić-Miočević. Proceedings of the International Conference, Šibenik 12th-15th September 2013, edited by Dino Demicheli, 209-222. Zagreb: University of Zagreb.

- Cowan, Ross, and Angus McBride. 2003. Imperial Roman Legionary AD 161-284. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- Dąbrowa, Edward. 1993. Legio X Fretensis. A Prosopographical Study of Its Officers (I-III c. A.D.). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Demicheli, Dino. 2015. “Conventus Linurnorum, conventus Scardonitanus.” Vjesnik za arheologiju i historiju dalmatinsku 108: 91-108.

- Dobson, Brian. 1974. “The Significance of the Centurion and ‘Primipilaris’ in the Roman Army and Administratio.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. Vol. II.1, edited by Hildegerd Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, 392-434. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Eck, Werner. 2003. “Hadrian, the Bar Kokhba Revolt and the Epigraphic Transmission.” In The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered. New Perspevtives on the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome, edited by Peter Schäfer, 153-170. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Fischer, Thomas. 2012. “Archaeological Evidence of the Marcomannic Wars of Marcus Aurelius (AD 166-80).” In A Companion to Marcus Aurelius, edited by Marcel van Ackeren, 29-44. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Gabričević, Branimir. 1953. “Novi natpisi iz Sinjske okolice.” Vjesnik za arheologiju i historiju dalmatinsku 55: 256-258.

- Goodman, Martin. 2008. Rome and Jerusalem. The Clash of Ancient Civilizations. London: Penguin Books.

- Gregori, Gian Luca. 2007. “Un anonimo governatore della provincia di Iudaea in un edito frammento Romano.” In Acta XII congressus internationalis Epigraphicae Graecae et Latinae, (Barcelona, 3.-8. 9. 2002), edited by Marc Mayer Olivé, Giulia Baratta and Alejandra Guzmán Almagro, 655-660. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona Institut d’Estudis Catalans.

- Gwinn, Christopher. 2013. “Lucius Artorius Castus Inscriptions – A Sourcebook.” Accessed March 10, 2013: http://www.christophergwinn.com/celticstudies/lac/lac.

- Hainzmann, Manfred. 1991. “Ovilava – Lauriacum – Virunum. Zur Problematik der Statthakterresidenzen und Verwaltungszentren Norikums ab ca. 170 n. Chr.” Tyche. Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte Papyrologie und Epigraphik 6: 61-85.

- Hudeczek, Erich. 1977. “Flavia Solva.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. Vol. II.6, edited by Hildegerd Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, 414-471. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Huskinson, Janet. 2015. Roman Strigillated Sarcophagi: Art and Social History. Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ibeji, Michael. C. 1991. The Evolution of the Roman Army during the Third Century AD. Birmingham: Faculty of Arts, University of Birmingham.

- Janeš, Andrej. 2009. “Antički stakleni nalazi.” In Tarsatički principij. Kasnoantičko vojno zapovjedništvo, edited by Nikolina Radić Štivić and Luka Bekić, 227-244. Rijeka: Grad Rijeka.

- Komoróczy, Balázs, Ján Rajtár, Marek Vlach and Claus-Michael Hüssen. 2020. “A Companion to the Archaeological Sources of Roman Military Interventions into the Germanic Territory North of the Danube during the Marcommanic Wars.” In Marcomanic Wars and Antonine Plague. Selected Essays on Two Disasters that Shook the Roman World / Die Markomannenkriege und die Antoninische Pest. Ausgewählte Essays zu zwei Desastern, die das Römische Reich erschüttetern, edited by Michael Erdrich, Balázs Komoróczy, Paweł Madejski and Marek Vlach, 173-254. Brno-Lublin: Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology, Brno, Instytut Archeologii, Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej, Lublin.

- Kienast, Dietmar. 2004. Römische Kaisertabelle. Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Kos, Peter. 2012. “The Construction and Abandonment of the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum Defence System in Light of the Numismatic material.” Arheološki vestnik 63: 265-300.

- Kovács, Peter. 2009. Marcus Aurelius’ Rain Miracle and the Marcomanic Wars. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

- Kusetič, Jure. 2020. “Claustra Alpium Iuliarum.” In Claustra patefacta sunt Alpium Iuliarum. Recent Archeological Investigation of the Late Roman Barrier System, edited by Josip Višnjić and Katharina Zanier, 12-37. Zagreb: Hrvatski restauratorski zavod.

- Liebs, Detlef. 1981. “Das ius gladii der römischen Provinzgouverneure in der Kaiserzeit.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 43: 217-223.

- Łuć, Ireneusz. 2020. “Emperor Commodus’ ‘Bellum desertorum’.” Res Historica 49: 61-95.

- Margetić, Lujo. 1990. Rijeka – Vinodol – Istra. Studije. Rijeka: Izdavački centar Rijeka.

- Maxfield, Valerie. A. 1981. The Military Decorations of the Roman Army. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Matei-Popescu, Florian. 2010. The Roman Army in Moesia Inferior. Bucharest: Conphys.

- –, and Ovidiu Tentea. 2006. “Participation of the Auxiliary Troops from Moesia Superior in Trajan’s Dacian Wars.” Dacia 50: 127-140.

- McLynn, Frank. 2009. Marcus Aurelius. A Life. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.

- Medini, Julijan. 1980. “Provincia Liburnia.” Diadora 9: 363-444.

- Miletić, Željko. 2014. “Lucius Artorius Castus i Liburnia.” In Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend. Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30th of March to 2nd of April 2012, edited by Nenad Cambi and John Matthews, 111-130. Split-Podstrana: Književni krug Split.

- Mócsy, András. 1974. Pannonia and Upper Moesia. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

- Mor, Menahem. 2016. The Second Jewish Revolt. The Bar Kokhba War, 132-136 CE. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

- Percan, Tihomir. 2009. “Antička fina keramika.” In Tarsatički principij. Kasnoantičko vojno zapovjedništvo, edited by Nikolina Radić Štivić and Luka Bekić, 69-98. Rijeka: Grad Rijeka.

- Petru, Peter and Jaroslav Šašel. 1971. Claustra Alpium Iuliarum. I – Fontes. Ljubljana: Narodni muzej v Ljubljani.

- Piso, Ioan. 1993. “Die senatorischen Amtsträge.” Vol. 1 of Fasti provinciae Daciae. Bonn: Dr Rudolf Habelt GmbH.

- Ritterling, Emil. 1924-1925. “Legio.” In PWRE, Vols. XII,1-XII,2, edited by Wilhelm Kroll, 1186-1837. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

- Saxer, Robert. 1967. “Untersuchungen zu den Vexillationen des römischen Kaiserheeres von Augustus bis Diokletian.” Vol. 1 of Epigraphische Studien. Köln-Graz: Böhlau Verlag.

- Sicker, Martin. 2001. Between Rome and Jerusalem. 300 Years of Roman-Judaean Relations. Westport-London: Praeger.

- Spaul, John Edward Houghton. 1994. Ala 2. The Auxiliary Cavalry Units of the Pre-Diocletianic Imperial Roman Army. Andover: Nectoreca Press.

- Spaul, John Edward Houghton. 2000. Cohors. The Evidence for and a Short History of the Auxiliary Infantry Units of the Imperial Roman Army. [BAR 841]. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Speidel, Michael Paul. 1987. “The Chattan War, the Brigantian Revolt and the Loss of the Antonine Wall.” Brittania 18: 233-237.

- Šašel, Jaroslav. 1954. “Add. ad CIL III 11675 Atrans, Nor.” Živa antika 4/1: 200-208.

- –, 1974. “Über Umfang und Dauer der Militärzone Praetentura Italiae et Alpium zur Zeit Mark Aurels.” Museum Helveticum: schweizerische Zeitschrift für klassische Altertumswissenschaft, 31/4: 225-233.

- –, 1992. Opera selecta. Ljubljana: Narodni muzej.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta. 2002. “The Boundary Stone between Aquileia and Emona.” Arheološki vestnik 52: 373-382.

- Thill, Elizabeth Wolfram. 2018. “Setting War in Stone: Architectural Depictions in the Column of Marcus Aurelius.” American Journal of Archaeology 122/2: 277-308.

- Urek, Maruša. 2020. “Ajdovščina (Castra) – Preliminary Results of the Investigation from 2017 to 2019.” In Claustra patefacta sunt Alpium Iuliarum. Recent Archeological Investigation of the Late Roman Barrier System, edited by Josip Višnjić and Katharina Zanier, 360-379. Zagreb: Hrvatski restauratorski zavod.

- Visy, Zsolt. 1988. Der pannonische Limes in Ungarn. Budapest: Corvina.

- Višnjić, Josip 2009. “Antička arhitektura.” In Tarsatički principij. Kasnoantičko vojno zapovjedništvo, edited by Nikolina Radić Štivić and Luka Bekić, 35-68. Rijeka: Grad Rijeka.

- Višnjić, Josip 2009a. “Amfore.” In Tarsatički principij. Kasnoantičko vojno zapovjedništvo, edited by Nikolina Radić Štivić and Luka Bekić, 121-152. Rijeka: Grad Rijeka.

- –, 2009b. “Antički metalni nalazi.” In Tarsatički principij. Kasnoantičko vojno zapovjedništvo, edited by Nikolina Radić Štivić and Luka Bekić, 153-182. Rijeka: Grad Rijeka.

- –, 2020. “Roman Tarsatica as Part of the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum System. The Results of Recent Archaeological Investigation.” In Claustra patefacta sunt Alpium Iuliarum. Recent Archeological Investigation of the Late Roman Barrier System, edited by Josip Višnjić and Katharina Zanier, 68-101. Zagreb: Hrvatski restauratorski zavod.

- Wade, Donald W. 1969. “Some Governors of Dacia: A Rearrangement.” Classical Philology 64/2: 105-107.

- Winkler, Gerhard 1977. “Noricum und Rom.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. Vol. II.6, edited by Hildegerd Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, 183-262. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Zaccaria, Claudio. 2002. “Marco Aurelio ad Aquileia e provvedimenti dopo la calata dei Marcomanni in Italia.” In Roma sul Danubio. Da Aquileia a Carnuntum lungo la via dell’ambra, edited by Maurizio Buora and Werner Jobst, 75-79. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Zaninović, Marin. 2011. “Tilurium, Aequum i Osinium. Arheološko-povijesna povezanost.” Kačić 41-43: 499-508.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0

International License 2004- 2024

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0

International License 2004- 2024