Introduction

Beatrice of Lorraine, marchioness of Tuscany – and mother of the more famous Matilda – died in Pisa on April 18th 1076 [1]. She died alone after a short illness: her daughter was not at her bedside. It was however Matilda who arranged the details of her mother’s burial and so Beatrice was entombed in the same Tuscan city where she died, in an ancient sarcophagus dated by art historians to the second century AD [2].

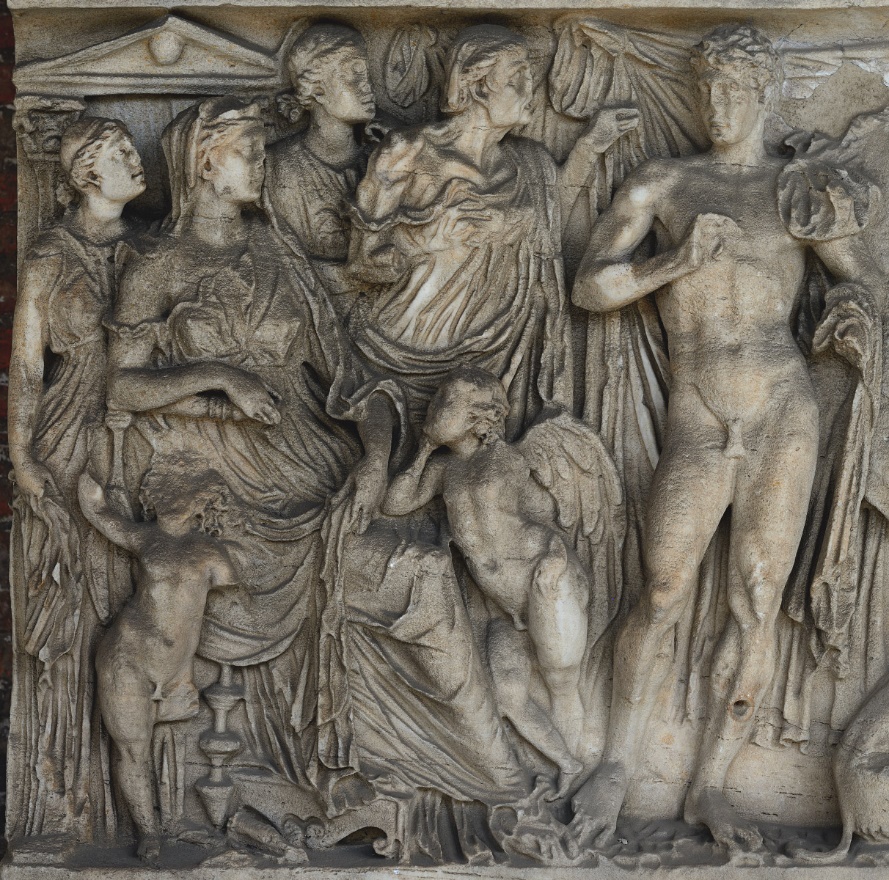

This tomb is today located in the Camposanto at Pisa, to which it was transferred at the very beginning of 19th century [3]: originally, it was located near the south wall of the Cathedral of Santa Maria. The choice of a Roman sarcophagus started what later became a real custom: Matilda’s choice was the first of its kind in Pisa, soon to be taken up by many other aristocrats, and was a choice steeped in the cultural mores of the period. In the second half of the 11th century there was, in point of fact, a taste for antiquity and the classic that foreshadowed the small Renaissance of the 12th century and which involved political language, a re-evaluation of Justinian law and the forms of architecture and plastic arts [Claussen 2008]. The sarcophagus that Matilda chose for his mother also acted, as it is well-known, as a model for Nicola Pisano when he had to carve the marble pulpit of the Baptistery of Pisa, in the middle of the 13th century [Tedeschi Grisanti 1995].

But what interests us now is not the artistic success enjoyed by Matilda’s choice. The purpose of this paper is instead to analyse her choice from the point of view of the relations between the two women, mother and daughter, and the possible significance that the image carved on that antìque marble – the legend of Phaedra and Hippolytus – may have had for Matilda herself.

The moment of the choice

In this perspective, the first problem that we face is that of being sure that we can ascribe to Matilda the choice of the sarcophagus.

We know that the decision to leave Beatrice’s body at Pisa was not appreciated by the monk Donizo who, laying aside for a moment his courtly manners, at the end of the first book of his poem dedicated to the forebears of the countess, appended some verses complaining that Canossa had been deprived of the earthly remains of Beatrice by a squalid, filthy city teeming with “marine monsters”: that is, with pagans, Turks, Libyans and suchlike [4]. Apparently, arrivals by sea evoked a certain anxiety even in those days [5]. Pisa, in short, was unworthy of safeguarding those earthly remains, which would certainly have found a much more commendable resting place on the pure white crag of Canossa [6].

Matilda’s choice of the sarcophagus is confirmed by three evidences, all from Pisa: they are, in order, an immunity privilege granted in favour of the canons of the cathedral of Pisa in 1100 [7], a donation decided by Matilda for the episcopate in the same year [8] and finally an epigraph, now lost, dating immediately after the Countess’s death [9].

Before beginning the examination of the documents, two short notes about the situation in Pisa when Beatrice died.

The city was devoid of the bishop: Guido da Pavia had died a few days before Beatrice, on the 8th of April. Matilda supported Pope Gregory VII in the choice of Landolfo, who came from Milan and was the abbot of the monastery of Nonantola. In August 1077, in Poggibonsi, she strengthened her support with a large, and a bit puzzling [10], donation of assets to the Pisan church [11], [Tirelli Carli 1977; Ronzani 1991], in which was asked to celebrate a mass per year for her mother [12].

The direct intervention in the March of Tuscany of Henry IV, who supported the cives of Pisa in their claim for broad autonomies from the marquis power, kept away for a long time Matilda from the city [13], although, from 1084 onwards, the vicecomes she had appointed, Ugo, returned to Pisa to exercise his functions. Matilda then supported the election of Bishop Daiberto (1088), not a pure “Gregorian”, but a man who could lead to concord in the city [Ronzani 2001, 131-132; Ciccopiedi 2016, 385-386]. During his absence from Pisa (from 1098: Daiberto participated in the crusade and became the first Latin patriarch of Jerusalem), Matilda granted to the canons the immunity [14] and gave the episcopacy a vast land belonging to the March [15], in order to subsidize the Cathedral of Santa Maria, under construction, defined in the document domum miris tabularum lapideis ornamentis incoeptam. In this donation, the dedication combines the love for Mary, mother of God, ob pium amorem beatę matris domini nostri sanctę Marię, with the suffrage for the soul of Beatrice, ob remedium animę matris meę beatę memorię Beatricis, and all her relatives, generically understood.

While the document in favor of the canons was issued in the marchional curtis of Pappiana, in the lower Valdiserchio, between Lucca and Pisa, the donation for the construction of the cathedral does not preserve the datatio topica, but the underlining of the aesthetic aspect that was assuming the cathedral, along with a brief notation “Nuper presentia nostra in civitate Pisę posita, delatum ad nostrę potestatis est ...”, contained in a donation in favor of Montecassino made at the same time [16], make us think that for the first time after the death of her mother, some 24 years later, Matilda eventually found herself in Pisa, where she could personally arrange the choice of the sarcophagus in line with the style of the classicist lapideis ornamentis of the new cathedral [17].

At that moment, at the very beginning of XII century, the sarcophagus was located against the exterior wall of the cathedral. In 1302 it was moved into the interior of the edifice [18], and subsequently moved to its definitive location in the Camposanto in 1810. Two years later, in 1812, Alessandro da Morrona, an erudite citizen of Pisa, published an inscription, today lost, dated 1116, that commemorates Matilda’s death and how she had arranged her mother’s burial and richly endowed the church that received her mother’s remains.

The first part of the epigraph, according to Ottavio Banti [19], is a copy of a text written shortly after the death of Matilda: “In the year of the Lord 1116, on the ninth day of the calends of August, died Lady Matilda, Countess of blessed memory, which for the soul of her mother, the venerable Lady Countess Beatrice, who rested in this tomb worthy of honor, magnificently endowed this church with assets located in many places. Their souls rest in peace” [20].

The Phaedra Question

Quite apart from Donizo’s complaints – who probably had never laid eyes on that tomb – what is perplexing to our contemporary eyes is the choice of subject reproduced on the sarcophagus Matilda chose for her mother. The story depicted on the surface of the sarcophagus concerns the young Hippolytus with whom Phaedra – his stepmother – fell in love, according to Euripides’ version of the story, taken up again with some important variants by Lucius Annaeus Seneca. Variants so significant that classical philologists who have dedicated themselves to the problem, maintain that Seneca based it on the now lost version of a tragedy by Sophocles, to wit – Hippolytus [Degl’Innocenti Pierini R. et al. (eds.) 2007].

In the version by Seneca, Phaedra, wife of the King of Athens, Theseus, falls madly in love with Hippolytus, the son that Theseus had had by his first wife, the queen of the Amazons. Encouraged by the nurse, Phaedra reveals her love for the young man and an indignant Hippolytus flees from the kingdom. Phaedra, wounded by his refusal, decides to take revenge and tells her husband that Hippolytus has tried to take advantage of her. A furious Theseus brings down a curse upon his son, who dies in a ghastly way, dreadfully gored during a boar hunt – that being, as son of an Amazon, his great passion. When Hippolytus’ corpse is brought back to the palace, Phaedra is so anguished that she confesses her crime to Theseus and kills herself.

In the sarcophagus bas-relief we find this story exactly narrated. We can see that the scene is divided into two: on the left, the figures of Phaedra, the splendid queen surrounded by her handmaidens, and of Hippolytus, a robust youth, are linked by the figure of the wet nurse, the matchmaker. Below, the two putti represent two different kinds of love: conjugal charity and Eros or carnal passion. On the right instead, the splendid scene of the hunt and, evident in the foreground, the boar that will gore Hippolytus.

A sin of incest?

The burial of Beatrice is accompanied by an inscription, remade at the time of the 19th century re-location [Franceschini 2000, p. 208], but which is already attested at the time of its first translation – in1302, as I said – when it was transcribed in a Pisan chronicle preserved in the State Archive of Lucca [21] and dated to the first half of the 14th century [22]. The epitaph reads «Quamvis peccatrix sum domna vocata Beatrix/ in tumulo missa iaceo quae comitissa» and may be translated in this way: «Though I am a sinner I was called Lady Beatrice. I, who was a Countess, now lie in this tomb» [23]. The second emistich of the second verse is otherwise handed down as «quamquam fuerim Comitissa», with the addition of a third verse: «Quilibet ergo pater noster, det pro mea anima ter», that is «Whoever wishes may say three Our Fathers for my soul» [Bertolini 1965, 361].

Not that there is anything wrong in recalling on a tombstone epitaph that the deceased was a sinner [24]: but the adjective in Latin rhymes with the name of the countess and the strong assonance, together with the chiasmus of the construction, confers a strong emphasis to the epitaph. Very different, by comparison, the small epitaph impressed on the illumination of Beatrice on the throne in the manuscript of Donizo: “May God grant that you dwell in the celestial halls, Beatrice” [25].

But, if she had indeed been a sinner, of what crime was Beatrice guilty? If the sarcophagus in which she was buried was chosen in the full awareness of what it represented, Beatrice’s sin was incest.

In a way of thinking far remote from – but still clung to – ours, in the 11th century Phaedra clearly represented incest in its unique mythical feminine profile [26]. Phaedra in fact, though she had no blood ties with Hippolytus, had dared to think of mixing in her womb the seed of two men who were father and son, thus risking to subvert the patrilineal order of the generation and, furthermore, risking to give birth to a monstrous being, fruit of the convergent generative capacity of two different seeds. The risk of producing deformed offsprings if the rules of sexual mores were not respected, was well understood in the 11th century. Peter Damian, in a letter [27] of 1064 sent to the abbot Desiderius of Montecassino, recounts the wicked marriage that the king of France, Robert (996-1031), had contracted with Berta, widow of Eude of Anjou, and his relative by blood. The two had generated a deformed son «anserinum per omnia collum et caput habentem» – who had, that is to say, the neck and head of a goose – and both, Roberto and Berta, had been excommunicated by almost all the bishops of Gaul [28].

The monumental tomb dedicated to Beatrice has always been interpreted as an extraordinary tribute to her mother by Matilda [29]. Matilda, afflicted by sorrow at the loss of her only point of reference and her model, by this burial would have made her mother into a “really true symbol of a cultural heroine” [30] with a sarcophagus symbolizing her “queenship and sacrality” [Franceschini 2004, 209]. And, indeed, it was a majestic burial, an extraordinary tribute to be seen, but only by those not able to read the sombre story graven there. Did Matilda, who commissioned the sepulchre, know Phaedra and her story?

To this question we can reply with a fair margin of probability: yes, Matilda, who was a cultivated woman, as many attestations show [Goetz 1994], could have easily known about Phaedra, and precisely Seneca’s version of Phaedra’s story. The tragedies of Seneca were copied throughout the early Middle Ages, but the oldest manuscript conserved is an 11th century codex probably produced in the Po Valley and transcribed before 1093, when it was listed among the manuscripts present in the library of the Monastery of Pomposa [31]. Seneca seems to have been an author familiar to the cultivated public: Peter Damian, for example, in different passages of his works, demonstrates that he knows well the Seneca tragedies [32].

The reuse of ancient sarcophagi

The fact that Matilda could easily know the story of Phaedra as told by Seneca is only a piece of our reconstruction. Another important element is the fact that her choice of re-using an ancient sarcophagus for her mother followed a relatively recent use for the Italic kingdom, imported for the first time in the peninsula by Pope Leo IX, the Lorenese Pope who used to call Beatrice «nepta nostra» because of their ties by blood [33]. It was in fact Leo IX the Pope who chose for himself a burial model new to the bishops of Rome, who until then had been inhumated, choosing a pilo marmoreo that was well in sight in the Vatican basilica, at the Ravenous door [Herklotz I. 2001, 142-144]. There is no clear information about the burials of his successors until Gregory VII, who, as well known, died in Salerno, where he was buried in the cathedral of the city, in a marmoreum tumulum [Herklotz I. 2001, 144-146]. The new style of monumental burial introduced by Leo IX emphasized, even after the death of the Popes, the papal primacy (the same primacy they pursued forcefully in those decades of the XI century), and attributed a royal connotation to their remains by recalling the funeral uses of the Carolingians since at least Carloman, Pippin’s son and brother of Charlemagne. The custom to redeploy sarcophagi from the Roman period for the burials of kings was born in fact with his funeral [34] and continued without interruption, except only for Louis II, who died in Italy, and was buried in the Basilica of Saint Ambrose in Milan. Not always, however, as in the case of Charlemagne, such sarcophagi, chosen in advance and transported to Aachen from Italy [Dierkens 1991, 166], remained visible after the burial: the sarcophagus of Charlemagne was buried below the ground, beneath the west entrance to the Aachen church [Dierkens 1991, 175-178; Nelson 2000, 145-151].

Regardless of whether or not they remained visible, one thing is certain: those sarcophagi were not randomly chosen and the sculptures carved on the marble had to emphasize those characters that the Carolingian kings considered the most suitable to represent them in their last resting place.

Thus the choice was already clear in the case of Carloman, whose sarcophagus, dating to the 4th century, was that of Jovinus consul and represented the consul himself and a «vivid depiction of a lion-hunt» [Nelson, 144-145]. Such images perfectly suited the representation of a king who wanted to be seen as the heir of the Roman authority and, at the same time, of his father Pippin’s military capabilities, embodied by hunting.

The sarcophagus of Charlemagne shows the abduction of Proserpina, interpreted by the Christian faith as the image of the soul rising to heaven. His son, Louis the Pious, had chosen a religious subject, which represented Moses’ flight from Egypt through the Red Sea: Walafrid Strabo had already acclaimed him as a new Moses, leading his people towards freedom. Next to Moses, Miriam became the representation of the wife of Louis the Pious, Judith [Nelson, 156].

In short, the images of the sculptures were read in the 9th century in an iconological manner: they were reinterpreted and adapted to the contemporary context [35] and to the subject that was to be commemorated. Their re-use thus shows a cultural operation of great awareness.

Matilda herself had chosen the sarcophagus of St. Anselm, who died in Mantua on March 18, 1086, a 5th century sarcophagus that represents the scene of the Triumph of Christ acclaimed by the apostles, and thus rightly placed Anselm - that Matilda would have liked to become Pope - among the new apostles [Calzona 2008, 42-43]. Finally, Matilda had carried marble arches to Canossa, to offer proper burial to her ancestors [36].

Regarding her mother’s sarcophagus, it is important to note that the choice of Matilda was not necessarily limited to the Pisan archeological remains.

As Arnold Esch had observed twenty years ago [37], the analysis of the stylistic forms and materials makes it possible to establish that many of the spolia in the Tyrrhenian coastal cities had a remote origin, namely they were chosen in Rome, Paestum, Pozzuoli, and then transported - with relative comfort - by sea.

In the specific case of Pisa, an inscription re-employed in the construction of the cathedral of Pisa names the College of Naval Blacksmiths of Ostia [Esch 1999, 83, note 16] and the figurative capitals of the cathedral were taken from the thermal baths of Caracalla or from the Basilica Neptuni in Rome [Tedeschi Grisanti 1990, 119-120].

The sarcophagus, selected in the vast Roman reservoir for its fine workmanship and for the story it told in its bas-reliefs, could have found a place in one of the transports towards the construction site of the cathedral. After all, as I said above, Matilda had had 24 years for choosing it.

The Hunt

If Matilda knew the story of Phaedra, why would she put it as a perpetual memory on her mother’s tomb, together with an inscription that emphasized a close relation between the lady’s name, Beatrix and the epitaph peccatrix?

Maybe there was a very good reason, such as the fact that the story outlined on the sarcophagus had many references to real incidents in the life of her late mother. In this sense, let us recollect a well known fact that in this context can be seen in a new light. Beatrice’s first husband, Boniface, actually died during a hunting party in 1052 at San Martino dell’Argine, or more precisely in the wood of Spineda [Bertolini 1971]. Antonio Falce, the author of the only biography of the margrave [Falce 1927], believed that it had not been an accident and that neither Henry III, nor Godfrey the Bearded were completely extraneous to this incident [Falce 1927, II, n. 82, 151-156]. Among the contemporary sources, however, only some narrations in the German area, such as the Annales Altahenses [38] and Hermannus Augiensis [39], attribute the death of Boniface to an ambush by some “milites”. Other contemporary authors such as Lambert von Hersfeld [40], Bonizone of Sutri [41] and Donizo [42] himself speak only of his death while hunting, with no comment about the possible culprits.

The death of Boniface opened a new chapter: from that moment on, it is no longer correct to speak of the house of Canossa in a dynastic sense, being better to call it Canossa-Lorraine [Lazzari 2012], a denomination that best describes the new order that strove to take over the dominions that had been ruled by Boniface. Two years after Boniface’s death, Beatrice remarried – this time her cousin Godfrey duke of Lorraine [Marrocchi 2002]. The marriage was considered by the Emperor Henry III an act of open rebellion: Godfrey of Lorraine was a quarrelsome rebel who had even dared destroy the city of Verdun in order to obtain ducal control of the whole of Lorraine, in the face of the wishes of his king [Marrocchi 2002]. Moreover, he married the widow of the margrave of Tuscany, thus creating a territorial and political axis under the control of the House of Ardennes that from Lorraine extended as far as Rome, and culminated in the election of Leo IX to the Chair of St Peter – he himself a member of the same dynasty. It was a new territorial order that directly threatened the imperial power, and Henry III was not slow in realizing it [Lazzari 2012].

Not only was the marriage violently opposed by the emperor, but it was also considered illegitimate under Canon Law: Beatrice and Godfrey were in fact cousins, relations to the 4th degree according to Germanic computations, that is the method adopted by Canon Law.

In a letter that Peter Damian addressed in 1057 to Beatrice excellentissimae duci [43], enthusiasm is shown at once, in the very first lines, for the public choice made by the married couple to keep their union chaste: a choice that impeded them from committing the sin of incest but also, in real terms, from having legitimate descendants [Lazzari 2012]. But as is known, even if Peter Damian did not mention it, they provided for the continuity of their union over time by arranging a sponsalicium, that is an engagement, between their respective children, Matilda and Godfrey [Lazzari 2012, note 67].

An unfortunate daughter

The union between Matilda and the son of her stepfather (likewise named Godfrey, the Hunchback), apparently caused fewer problems from the point of view of the canonic regulations compared to that of their respective parents: the two were indeed comprivigni, that is, step-children, and neither the canonic norm nor the civil code forbade unions of this kind [Lazzari 2012]. But, the children of two cousins, in any case remained related by a familial relationship of the 5th degree, too close for the norms that the Lateran Council of 1059 had set down, which forbade unions up to the 7th grade [44] computed “per genicula” [45].

For the two protagonists, this union proved itself to be anlucky. The young couple remained engaged for 14 years, an extremely long time, especially considering the normal employ of the full reproductive period of women at the time: Matilda and Godfrey could marry only at Verdun in December of 1069, when the death of Godfrey the Bearded had dissolved the relation between their parents, [Bertolini 1965]. Matilda at the time was 23 years old. She stayed in Lorraine with her husband while her mother returned to the Italic kingdom where she undertook in person the government of the dominions of the House of Canossa-Lorraine. Beatrice assumed immediately the role of dux of Tuscany, legitimized by the recognition of Pope Alexander II who, on 13 January 1070 – and Godfrey had died just a month before – in the act of taking the Monastery of Santa Trinità di Torri in the Siena area under his protection – declared that he was doing so especially “interventu Beatricis ducatricis” [Goetz 1995, 214].

Matilda’s marriage only lasted a short time: she had a daughter, an unfortunate baby who was given the name Beatrice, and who died shortly after birth. It was after that delivery and the death of the baby that Matilda returned to Italy and never wished to meet her husband ever again. Hardly two years after the marriage, the records already attest his presence in Mantua [46].

The Separation

The reason for such an unusual and definitive separation has been the object of myriad conjectures, yet it is surely destined to remain shrouded in mystery. Certainly, it does not seem credible that a woman belonging to the highest aristocracy of the empire would have deserted her husband simply because he was deformed, as it has been repeated many times. Nor that Matilda had difficulty in adapting herself to the conjugal relationship in what she felt was a hostile ambience, as it has been recently asserted [47]: there is no data to substantiate such hypotheses and it is hard to understand why the lady should have considered hostile an ambience in which she had lived for many years, and in which she had been raised.

I should like to propose a hypothesis that, even though still difficult to prove, tries to put together the evidence that I have presented here. I believe that the explanation can be found in what were believed to be the grievous transgression of incest and its dramatic consequences for the offspring. Matilda did not reject marriage, but separated from her husband only after the birth – and immediate death – of the baby daughter that she had borne and that possibly was not sufficiently well-formed to survive. In the Chronicon of Saint Hubert [48], a contemporary Lorraine source, it is explicitly stated that the lady from then onwards refused Godfrey his “maritalem gratiam”, in a word – sexual intercourse.

Godfrey tried to join her in Italy in 1073. He was welcomed by Beatrice [Golinelli 2008], but for this reason Matilda distanced herself definitively from him, and from her mother. We may draw still further evidence of Matilda’s state of mind and her relations with her mother from the correspondence of Gregory VII. In early January 1074, the pope urged Matilda come to Rome together with her mother: an invitation which the lady did not accept [49]. Also, he asked her not to embrace the monastic life: the role to which she was called in the world was quite another [50]. In a letter written just a month later [51], Gregory exhorted her “ne illos desereres”, not to abandon her mother and her husband and, with great affection, the pope urged Matilda to return to taking communion, a cure for the soul she simply could not do without [52]. And he counselled her to trust herself to Holy Mary, who “altior et melior ac sanctior est omni matre”, is greater, better and saintlier than any other mother [53]. “I promise you without any doubt – the pope ends the letter – that you will find her readier than an earthly mother and more affectionate in her love for you” [54].

Matilda finally accepted the pope’s invitation to draw closer to her mother, but not to her husband, as it is demonstrated by the welcome that the two women shared together, a couple of months later, on the Easter of that same year [55], to Theodoric II, abbot of the monastery of St. Hubert in the Ardennes and to Herman, bishop of Metz, who accompanied him. The chronicle of the monastery of St. Hubert tells that the two men were going to Rome to gain Gregory VII’s support in the dispute that opposed them to Godfrey the Hunchback, reluctant to give effect to the donations that his father had decided in favor of the abbey shortly before his death [56].

Beatrice and Matilda invited the abbot and the bishop of Metz to go to Pisa [57], where they were greeted with great pomp, and together with seven other bishops – among them St. Anselm of Baggio [Ceccarelli 2016, 357] – celebrated the Easter solemnities [58].

But the relationship between mother and daughter seems hopelessly spoiled, for what we can guess from documentary evidences, which see they drifting apart, and even more, their encounter opportunities. What was then the blame that Matilda attached to her mother? That of having first wished and promoted, and then supported – even against the clear evidence of the error – an illicit marriage, undermined from the outset by the far too close consanguinity between the two spouses. We recall that, on the basis of Gregory VII’s letter, Matilda no longer took communion and the pope used all his persuasive power and all his doctrine to persuade her to resume religious practice: it is evident that the young woman felt stained with such a serious sin that she could no longer receive the sacrament. Religion in the hardest years of the reform of the Church weighed heavily – we saw that through Pier Damian’s testimony [59] – on unions considered unlawful. Even if her marriage had the pope’s full blessing, the biological result of that union must have shown Matilda that there was something amiss, and the facts spoke for themselves.

In the last year of Beatrice’s life, mother and daughter met very seldom [60], and Beatrice – as we mentioned at the beginning – died in Pisa, alone. In the sarcophagus that Matilda planned for her, the death of the father while hunting featured as the beginning of a tragedy, marked by the curse of incest, which Beatrice herself – like Phaedra – committed by marrying her cousin Godfrey, but did not consume, leaving it to her daughter to bear the consequences, and pay the price.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Annales Altahenses maiores, Giesebrecht W., von Oefele E. L. B. (eds.), MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, 4, Hannover 1890.

- Banti O. 2000, Monumenta Epigraphica Pisana saeculi XV antiquiora, Pisa, 2000 (Biblioteca del «Bollettino Storico Pisano». Fonti, 8).

- Bonizonis Sutriensis Liber ad Amicum, E. Dümmler (ed.), MGH, Libelli de lite, Hannover 1891, pp. 568-620.

- Chronicon Sancti Huberti Andaginensis, Bethmann L. C., Wattenbach W. (eds.), in MGH Scriptores in Folio, 8, Hannover 1848, pp. 565-630.

- Donizone, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, Golinelli P. (ed.), Milano: Jaca Book, 2008.

- Die Briefe des Petrus Damiani, Reindel K. (ed.), MGH, Epistolae, II: Die Briefe der deutschen Kaiserzeit, 4. I-IV, München 1983-1993.

- Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde von Tuszien, Goez E., Goez W. (eds.), MGH, Laienfürsten- und Dynastenurkunden der Kaiserzeit, 2, Hannover 1998.

- Le epigrafi e le scritte obituarie del Duomo di Pisa, Banti O. (ed.), Pisa, 1996 (Biblioteca del « Bollettino Storico Pisano ». Fonti, 5).

- Gregorii VII registrum, Caspar E. (ed.), MGH, Epistolae selectae in usum scholarum, II/2, Berlin 1923.

- Lamperti monachi Hersfeldensis Opera, Holder-Egger, O. (ed.), MGH, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, 38, Hannover 1894.

- Herimanni Augiensis Chronicon, Pertz G. H. (ed.), MGH, Scriptores in Folio, 5, Hannover 1844, 67-133.

- Nicolai II Synodica generalis, Weiland L. (ed.), MGH, Legum sectio IV, Constitutiones et acta publica imperatorum et regum, 1, Hannover 1893, 546-548.

- Pier Damiani, De gradibus parentelae, in Patrologiae cursus completus. Series Latina, Migne J.-P. (ed.), Paris 1853, CXLV, coll. 191-204.

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, et architettori, 1-2, Firenze: Giunti, 1568.

Secondary sources

- Banti O. 1996, Le epigrafi e le scritte obituarie del Duomo di Pisa, Pisa: Pacini.

- Bertolini M.G. 1965, Beatrice, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, VII, Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 352-363, ora in Bertolini M.G. 2003, Studi canossiani, O. Capitani, P. Golinelli (eds.), Bologna: Patron, 2003, 169-183.

- - 1971, Bonifacio marchese e duca di Toscana, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, XII, Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 96-113, ora in Bertolini M.G., Studi canossiani, O. Capitani, P. Golinelli (eds.), Bologna: Patron, 2003, 184-208.

- - 1994, I Canossiani e la loro attività giurisdizionale con particolare riguardo alla Toscana, in Golinelli P. (ed.), I poteri dei Canossa. Da Reggio Emilia all’Europa, Atti del convegno internazionale di studi (Reggio Emilia – Carpineti, 29-31 ottobre 1992), Bologna: Pàtron, 99-141, ora in Bertolini M.G., Studi canossiani, O. Capitani, P. Golinelli (eds.), Bologna: Patron, 2003, 41-84.

- Bettini M. 2002, Fedra e il corto circuito della consanguineità, in «Dioniso» 1, 88-99, ora in Bettini M. 2009, Affari di famiglia. La parentela nella letteratura e nella cultura antica, Bologna: Il Mulino, 221-238.

- Calzona A. 2008, L’altercatio tra Mantova e Canossa: immagini ‘diverse’ al servizio della Riforma, in Calzona A. (ed.), Matilde e il tesoro dei Canossa tra castelli, monasteri e città, Milano: Silvana Editoriale, 20-49.

- Ceccarelli Lemut M.L. 2016, La dimensione marittima della marca di Tuscia, in Matilde di Canossa e il suo tempo, Atti del XXI Congresso internazionale di studio sull’alto Medioevo in occasione del IX Centenario della morte (1115-2015), San Benedetto Po - Revere - Mantova - Quattro Castella, 20-24 ottobre 2015, Spoleto: CISAM, 355-370.

- Claussen P.C. 2008, Scultura e splendori del marmo a Roma nell’età della Riforma ecclesiastica nell’XI e XII secolo, in Calzona A. (ed.), Matilde e il tesoro dei Canossa tra castelli, monasteri e città, Milano: Silvana Editoriale, 202-2115.

- Ciccopiedi C., Matilde e i vescovi, in Matilde di Canossa e il suo tempo, Atti del XXI Congresso internazionale di studio sull’alto Medioevo in occasione del IX Centenario della morte (1115-2015), San Benedetto Po - Revere - Mantova - Quattro Castella, 20-24 ottobre 2015, Spoleto: CISAM, 371-390.

- Degl’Innocenti Pierini R. et al. (eds.) 2007, Fedra: versioni e riscritture di un mito classico, Firenze: Edizioni Polistampa.

- Dierkens A. 1991, Autour de la tombe de Charlemagne. Considérations sur les sépoltures et les funérailles des souverains carolingiens et des membres de leur famille, in Dierkens A., Sansterre J.-M. (eds.), Le souverain à Bysance et en Occident du VIII au X siècle, «Byzantion», 61, 156-80.

- Dierkens A. 2003, Les funérailles royales carolingiennes, in Dierkens A. and Marx J. (eds), La sacralisation du pouvoir. Images et mises en scène (= Problèmes d’Histoire des Religions, XIII/2003). Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 45-58.

- Dierkens A. 2004, Ad instar illius quod Beseleel miro composuit studio. Éginhard et les idéaux artistiques de la «Renaissance carolingienne», in Sansterre J.-M. (ed.), L’autorité du passé dans les sociétés médiévales. Rome, École Française de Rome et Bruxelles, Institut Historique Belge de Rome (Collection de l’École Française de Rome, 333 ; = Bibliothèque de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome, LII), 339-368.

- Dierkens A. 2009, Quelques réflexions sur la présentation des sarcophages dans les église du haut Moyen Âge, in Alduc-Le Bagousse A. (ed.), Inhumations de prestige ou prestige de l’inhumation? Expressions du pouvoir dans l’audelà (IV-XV siècle), Caen: C.R.A.H.M., 265-302, in particolare pp. 279-87

- Esch A. 1999, Reimpiego dell’Antico nel Medioevo: la prospettiva dell’archeologo, la prospettiva dello storico, in Ideologie e pratiche del reimpiego nell’alto medioevo, Atti della XLVI Settimana del CISAM, Spoleto: CISAM, 73-108.

- Falce A. 1927, Bonifacio di Canossa, padre di Matilde, Reggio-Emilia.

- Franceschini F. 2004, Beatrice e Matilde di Canossa. Tra il sarcofago di Fedra e il Purgatorio Dantesco. Su una “bizzarra” interpretazione di Francesco da Buti, in «Rivista di Studi Danteschi», IV, 205-216.

- Franzoni C. 2008, Arcae marmoreae: le antichità nel tempo di Matilde, in Calzona A. (ed.), Matilde e il tesoro dei Canossa tra castelli, monasteri e città, Milano: Silvana Editoriale, 84-95.

- Goetz E. 1994, Matilde di Canossa e i suoi ospiti, in Golinelli P. (ed.), I poteri dei Canossa. Da Reggio Emilia all’Europa, Atti del convegno internazionale di studi (Reggio Emilia – Carpineti, 29-31 ottobre 1992), 325-333.

- - 1995, Beatrix von Canossa und Tuszien. Eine Untersuchung zur Geschichte des XI. Jahrhunderts, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke.

- Golinelli P. 2008, Matilde di Canossa, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 72.

- Herklotz I. 2000, Gli eredi di Costantino. Il papato, il Laterano e la propaganda visiva nel XII secolo, Roma: Viella.

- Herklotz I. 2001, “Sepulcra” e “Monumenta” del Medioevo. Studi sull’arte sepolcrale in Italia, Napoli: Liguori.

- Lauwers M., Treffort C. 2009, De l’inhumation privilégié à la sépulture de prestige. Conclusions de U table ronde, in Alduc-Le Bagousse A. (ed.), Inhumations de prestige ou prestige de l’inhumation? Expressions du pouvoir dans l’audelà (IV-XV siècle), Caen: C.R.A.H.M., 439-50.

- Lazzari T. 2012, Goffredo di Lorena e Beatrice di Toscana, in Cantarella G.M. e Calzona A. (eds.), La reliquia del sangue di Cristo. Mantova, l’Italia e l’Europa al tempo di Leone IX, Verona, pp. 225-242.

- Les sarcophages de l’Antiquité tardive et du haut Moyen Age : de la fabrication à la diffusion, Actes des XXXe journées Internationales d’Archéologie Mérovingienne (Bordeaux 2-4 octobre 2009), a cura di I. Cartron, F. Henrion, C. Scuiller, supplément à la revue Aquitania, Bordeaux, à paraître 2013.

- MacGregor A.P. 1985, The Manuscripts of Seneca’s Tragedies. A Handlist, in «Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt», II 32.2, 1135-1241.

- Manarini E. 2016, Ai confini con l’Esarcato: proprietà, possessi e giurisdizioni dei Canossa nel Bolognese orientale, in Matilde di Canossa e il suo tempo, XXI congresso internazionale di studio del CISAM (San Benedetto Po, Revere, Mantova, Quattro Castella, 20-24 ottobre 2015), Spoleto, 459-482.

- Marrocchi M. 2002, Goffredo il Barbuto, duca di Lotaringia e marchese di Toscana, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, LVII, Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, pp. 533-539.

- Morrona A. 1812, Pisa illustrata nelle arti del disegno, Livorno.

- Nelson J.L. 2000, Carolingian royal funerals, in Theuws F., Nelson J.L. (eds.) Rituals of power: from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, Leiden-Boston-Köln: Brill (The Transformation of the Roman World, 8), pp. 131-183.

- Ronzani M. 1991, Pisa fra Papato e Impero alla fine del secolo XI: la questione della “Selva del Tombolo” e le origini del monastero di S. Rossore, in Pisa e la Toscana occidentale nel Medioevo: a Cinzio Violante nei suoi 70 anni, I, Pisa, 173-230.

- - 1997, Chiesa e «Civitas» di Pisa nella seconda metà del secolo XI. La situazione interna ed i rapporti con il Papato, l’Impero e la Marca di Tuscia dall’avvento del vescovo Guido all’elevazione di Daiberto a metropolita di Corsica (1060-1092), Pisa.

- - 2001, Vescovi e città a Pisa nei secoli X e XI, in Vescovo e città nell’alto medioevo: quadri generali e realtà toscane, Atti del Convegno internazionale di Studi (Pistoia - 16-17 maggio 1993), Pistoia: Società pistoiese di storia patria, 93-132.

- Tedeschi Grisanti G. 1990, I marmi romani di Pisa. Problemi di provenienza e di commercio, in Dolci E. (ed.), Atti del seminario Il marmo nella civiltà romana, Lucca, pp. 116-125.

- Tedeschi Grisanti G. 1995, Il sarcofago della marchesa Beatrice di Toscana, in Peroni, A. (ed.), Il Duomo di Pisa, Modena, 592-594.

- Tirelli Carli M. 1977, La donazione di Matilde di Canossa all’episcopio pisano, in Bollettino storico pisano, 46, 139-159.

- Trillitzsch W. 1978, Seneca tragicus — Nachleben und Beurteilung im lateinischen Mittelalter von der Spätantike bis zum Renaissancehumanismus, in «Philologus. Zeitschrift für antike Literatur und ihre Rezeption», 122/1-2, 120–136.

Notes

1. Goez 1995; Bertolini 1965. Even the lemma Bonifacio marchese e duca di Toscana is, of course, very useful: Bertolini 1971.

2. A complete description of the sarcophagus and the events that involved it, its original location and the subsequent movements that it suffered, can be read in Tedeschi Grisanti 1995, with a complete previous bibliography.

3. At the beginning of the 14th century, during the construction of gradule (the steps of the parvis), the sarcophagus was moved first inside the cathedral and then back outside, in the fourth blind arch of the south side of the grandstand, where now is the epigraph that remember it. For a new hypothesis, not entirely convincing, about a primitive placement in front of the episcopal palace, see Calzona 2008, 49, note 107.

4. Donizone, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, 120, vv. 1368-1372: «Dolor hic me funditus urit / Cum tenet urbs illam quae non est tam bene digna. / Qui pergit Pisas, videt illic monstra marina. / Haec urbs paganis, Turclis, Libicis quoque Parthis, / Sordida! Chaldei sua lustrant litora tetri».

5. About the maritime dimension of the march of Tuscany and the Mediterranean projection of its marquis, see Ceccarelli Lemut 2016.

6. Donizone, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, 120: vv. 1373-1375: «Sordibus a cunctis sum munda Canossa! Sepulcri / Atque locus pulcher mecum! Non expedit urbes / Quaerere periuras, patrantes crimina plura».

7. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 61, 186-188.

8. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 63, 190-192. The document is dated by the publisher the year 1100, between January 1 and September 24.

9. About this epigraph, see below, notes 19 and 20.

10. They were all assets placed in the diocese of Bologna: over 600 mansi, organized in a number of curtes and a castle, all located on the Bolognese Apennines, which were granted half to the elected bishop Landolfo, and the other half to the cathedral canons, as long as they lived together and chastely. For a recent analysis, which helps to clarify the complex strategy of Matilda, see Manarini 2016.

11. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 23, 87-92.

12. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 23, 91: «Insuper et anc condictionem supradicto tenore episcopo imponimus, ut annualiter anniversarium matris mee Beatricis honorifice celebret pro mercede anime patris mei matrisque mee et mee sine omni mea et heredum ac proheredum meorum contradictione vel repetitione».

13. On the situation of Pisa in that course of time see Ronzani 1997, 131-136.

14. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 61, 186-188.

15. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 63, 191: «Dum ad dei honorem eiusque pię genitricis Mariae gloriosum triumphum Pisanę ecclesię curam quondam cum nostris [fidelibus hab]eremus eiusque domum miris tabularum lapideis ornamentis incoeptam, qualiter ad effectum perducere dignis possemus auxiliis, sedula mentis intentione animo cotidie volveremus, tam pro nostra quam matris nostrę ibi quiescentis anima concessimus illius ecclesię ad operam perficiendam vel ad aliquam restaurationem post peractum opus forte [...]faciendam campum iuris marchię iuxta palatium situm, cuius caput a meridie in Arnum fluvium terminatur, secundum latus ab oriente strata intercurrens terminat, tercium vero terra Baruncelli, quartum autem terra marchię, eo videlicet modo, ut campus debeat habitari et habitantium pensio et alicuius honoris [red]ditio ad opus fabricę construendum vel restaurandum debeat similiter annue persolvi et dari».

16. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 62, 188-190, 190.

17. I think it is unlikely that Beatrice had chosen herself the sarcophagus for her burial, as there is no Beatrice’s donation in favor of the Pisan church for her own suffrage. At the time of her death, the cathedral was already under construction.

18. The text of the plaque that remembers the translation is already reported by Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, 1, 98: «Anno Domini MCCCIII. sub dignissimo Operario D. Burgundio Tadi occasione graduum fiendorum per ipsum circa ecclesiam supradictam tumba superius notata bis translata fuit, nunc de sedibus primis in ecclesiam, nunc de ecclesia in hunc locum, ut cernitis, (excellentem)». The use of the “Pisan style” in the dating of the inscription requires attributing it to 1302.

19. Banti 1996, nn. 38-39, 49-50.

20. Morrona 1812, vol. II, 316: «AN. DNI. MCXVI. KLAS AUG. OBIIT DNA / MATILDA FELICIS MEMORIE COMITISSA / QUE PRO ANIMA GENETRICIS SUE DNE / BEATRICIS COMITISSE VENERABILIS IN HAC / TUMBA HONORABILI QUIESCENTIS / IN MULTIS PARTIBUS MIRIFICE HANC / DOTAVIT ECLAM QUARUM ANIME / REQUIESCANT IN PACE».

21. Archivio di Stato di Lucca, ms. 54, c. 24r.

22. Franceschini 2000, p. 208 and note 17 about the datation of the chronicle.

23. Banti 2000, n. 2, 17-18: «†/ QUAMVIS PECCATRIX SUM DOMNA VOCATA BEATRIX/ IN TUMULO MISSA IACEO QUAE COMITISSA/ A(nno) D(omini) MLXXVI».

24. Although it is not customary: a quick search for the lemma “peccat *” in the various volumes of the MGH Antiquitates collection shows that the term never occurs in the epitaphs, and very rarely in recordings of Libri memoriales.

25. Ms. Vat. Lat. 4922, c. 30v: «Det Deus in claris cameris tibi stare Beatrix».

26. On the meaning of Fedra’s guilt and on the conception of incest in the Roman tradition, see Bettini 2002, 221-238.

27. Die Briefe des Petrus Damiani, III (1989), n. 102.

28. Die Briefe des Petrus Damiani, III (1989), n. 132: «Nam Robertus Gallorum rex, avus istius Philippi, qui in paterni iuris sceptra successit, propinquam sibi copulavit uxorem, ex qua suscaepit filium, anserinum per omnia collum et caput habentem. Quos etiam virum scilicet et uxorem, omnes fere Galliarum episcopi communi simul excommunicavere sententia».

29. See, with rich earlier literature, the recent Franzoni 2008, 85-87.

30. Franceschini 2004, 207-208: «l’utilizzazione dello splendido sarcofago, che inaugura la tradizione delle sepolture eccellenti, e la pubblica celebrazione annuale di Beatrice, fanno di questa una figura di eroe culturale della città».

31. In the latest critical edition of Seneca’s tragedies (Pisa 2007), curator Giancarlo Giardina recalls that tragedian Seneca has a tradition of over 397 codes, a tradition that is divided into two branches, E and A.

32. On the success of tragedian Seneca in the Middle Ages, see Trillitzsch 1978, 126-127 about Peter Damian.

33. Bertolini 1965, 171: «Il 19 luglio 1050 Leone IX concesse la protezione della Sede apostolica all’abate Bonatto dei monastero di S. Salvatore dell’Isola (diocesi, di Siena), “inclinati precibus tuis et maxime neptis nostrae Beatricis ducatricis”».

34. Nelson 2000, 143-145, 145: «Burial in a reused Roman sarcophagus was an innovation, as far as we know, for Frankish royalty».

35. Against an iconographic reading, instead, Franzoni 2008, 87.

36. Donizone, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, 2, 5-10: «Cum ad clarorum principum mausoleum iam per quinque lustra nostra resideret humilitas, nullamque ex eis videret memoriam quod apicum commendaret perpetuitas, accidit quando nuper vestri honoris sublimitas Canossam deduci arcas iussit marmoreas ad tumulandum dignius eorum corpora ut ea quae ex eis a senibus et veracioribus nostris temporibus viris, nostra audierat parvitas, ferventi zelo carmine heroico nostra temptaverit carazare imperitia, ne tantorum heroum laterent acta fortia et illustrissima». About these sarcophagi, see Franzoni 2008, 88-89.

37. In the opening paper of the XLVI Settimana del Cisam: Esch 1999, 82-83.

38. Annales Altahenses, 48: «Bonifacius marchio de Italia insidiis cuiusdam militis sui occiditur».

39. Herimanni Chronicon, 131: «Bonifacius, ditissimus Italiae marchio, immo tyrannus, insidiis a duobus exceptus militibus sagittisque vulneratus et mortuus, Mantuae sepelitur».

40. Lamperti Opera, Annales, 64: «Marchio Italorum Bonifacius obiit; cuius viduam Beatricem dux Gotefridus accipiens, marcham et caeteras eius possessiones coniugii pretextu sibi vendicavit».

41. Bonizonis Liber ad Amicum, 590: «Huius pontificis tempore moritur inclitus dux et marchio Bonifacius, parvulos relinquens heredes».

42. Donizone, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, 373-374, vv. 1123-1127: «Sed complere nequit, quia mors non hoc sibi cedit, / Ipse die sexta Madii post quippe Kalendas / Deseruit terram; quem Christus ducat ad ethram. / Quando defunctus terrae datus estque sepultus, / tunc quinquaginta duo tempora mille Dei stant».

43. Die Briefe des Petrus Damiani, II, n. 51, 132: «De misterio autem mutuae continentiae, quam inter vos Deo teste servatis, diu me fateor duplex opinio tenuit, ut virum quidem tuum arbitrarer hilariter hoc pudicitiae munus offerre, te vero gignendae prolis desiderio non hoc libenter admittere. Sed cum gloriosus idem vir nuper michi ante sacrosanctum corpus beati apostolorum principis intimasset sanctum desiderium tuum et pudicitiae perpetuo conservandae propositum, fateor: Laetatus sum in his, quae dicta sunt michi et exultavi vehementer. Iam siquidem solutum est in te illud antiquae maledictionis elogium, quo primae mulieri dictum est: Sub viri potestate eris, et ipse dominabitur tui».

44. Nicolai II Synodica generalis, 548: «11. Ut de consanguinitate sua nullus uxorem ducat usque ad a generationem septimam vel quousque parentela cognosci poterit».

45. The seventh grade, calculated “by genicula”, is equivalent to the fourteenth according to the Roman calculus. The council took up the arguments voiced against the Roman calculus by Pier Damiani, De gradibus parentelae, coll. 191-204.

46. Die Urkunden und Briefe der Markgräfin Mathilde, n. 1, 31-35.

47. Golinelli 2008: «Furono mesi molto duri per la difficoltà di M. ad adattarsi al rapporto coniugale in un ambiente che sentiva ostile, per cui, appena le fu possibile, fuggì e tornò presso la madre».

48. Chronicon sancti Huberti Andagimensis, 583.

49. Gregorii VII registrum, I, n. 40, 62-63, 1074, January 3: «Quapropter si contigerit gloriosam matrem vestram hoc tempore Romam redire, toto corde ammonemus immo rogamus claritatem vestram ad visitationem apostolorum cum eadem venire, nisi forte aliquid instet, quod vos non pretermittenda necessitate detineat».

50. Gregorii VII registrum, I, n. 40, 62-63: «Sed noverit prudentia vestra honestis inceptis religiosisque inchoationibus opus esse honestiori perseverantia atque Deo opitulante religiosissima consummatione».

51. Gregorii VII registrum, I, n. 47, 71-73, 1074, February 16, 71: «Tu tamen, si pensare non neglegis, ut reor, animadvertis, quia pro tantis tui curam me oportet habere, pro quantis te caritatis studio detinui, ne illos desereres, ut tuę solius animę saluti provideres».

52. Gregorii VII registrum, I, n. 47, 72: «Sed quia inter cętera, quae tibi contra principem mundi arma Deo favente contuli, quod potissimum est, ut corpus Dominicum frequenter acciperes, indicavi et, ut certę fiducię matris Domini te omnino committeres, precepi, quid inde beatus Ambrosius, videlicet de sumendo corpore Domini, senserit, his in litteris intimavi». And then, later, 73: «Debemus, o filia, ad hoc singulare confugere sacramentum, singulare appetere medicamentum. Hęc ideo, karissima beati Petri filia, scribere procuravi, ut fides ac fiducia in accipiendo corpus Domini maior tibi accrescat».

53. Gregorii VII registrum, I, n. 47, 73: «De matre vero Domini, cui te principaliter commisi et committo et nuaquam committere, quousque illam videamus, ut cupimus, omittam, quid tibi dicam, quam cęlum et terra laudare, licet ut meretur nequeant, non cessant? Hoc tamen procul dubio teneas, quia, quanto altior et melior ac sanctior est omni matre, tanto clementior et dulcior circa conversos peccatores et peccatrices».

54. Gregorii VII registrum, I, n. 47, 73: «Pone itaque finem in voluntate peccandi et prostrata coram illa ex corde contrito et humiliato lacrimas effunde. Invenies illam, indubitanter promitto , promptiorem carnali matre ac mitiorem in tui dilectione».

55. Easter, which in 1074 corresponded to April 20.

56. Chronicon Sancti Huberti Andaginensis, 583: «Coactus tandem abbas de eo desperare, ut erat amicissimus domino Herimanno Metensium episcopo, disposuit cum eo Romam ire, volens de eventu rerum papam Gregorium VII consulere, et inter eundum de eisdem agere cum marchissa Beatrice. Ingressi viam Romae pasca celebrare certabant, sed tardantibus eos quibusdam, qui obsonia episcopo certatim impendebant, ad Lunensem portum pervenerunt maioris hebdomadae feria quinta».

57. Chronicon Sancti Huberti Andaginensis, 583: «Ibi occurrit illis legatus marchissae Beatricis, cum precibus etiam filiae eius Mathildis, ut Pisas diverterent, ut apud eas proximum pasca sollempnizarent». About this episode see Ronzani 1997, 133-135 e Ceccarelli Lemut 2016, 357.

58. Chronicon Sancti Huberti Andaginensis, 583-584: «Sic divertentes Pisas honorabiliter suscepti sunt a matre et a filia, satis eminentiores ceteris curialibus habiti in eadem curia. In exsolvendis pascalibus officiis convenerant ibi septem episcopi, hiisque omnibus postpositis celebritas missarum dominicae resurrectionis oblata est agenda Herimanno Metensium episcopo. Vide res praeter saecularium confluentium multiplices glorias, clericorum diversi ordinis frequentiam, ecclesiastici ministerii vasa auri et argenti quamplurima, diversi apparatus vestes peregrinas, Beatricem et Mathildem procedentes quasi cuiusdam dominationis praefecturas».

59. See note 29.

60. See Bertolini 1994, 103-104, note 17.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0

International License 2004- 2026

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0

International License 2004- 2026